To Save Western U.S. Forests, Cut Them Way Back, Study Suggests

(Bloomberg) -- A new study proposes a radical prescription for the ailing health of dry U.S. Western forests: cutting back trees by as much as 80%.

The study suggests that forests in the Sierra Nevada and nearby ranges could better withstand severe wildfire, drought, infestations and climate change if the density of trees was dramatically reduced. That would shut out competition for water and other resources, helping remaining trees weather an array of stresses. The study appears in next month’s edition of and adds to a live debate about how to protect fragile forest ecosystems as climate change exacerbates threats.

“This is a fundamentally different approach to growing and managing forests,” said lead author Malcolm North, a U.S. Forest Service research ecologist and professor at the University of California, Davis.

For the past century, U.S. foresters have largely aimed to maximize the number of trees they can grow in an area and guard them from flames. Yet decades of suppressing wildfires in ecosystems that have adapted to regular, low-severity burns have left many forests thickly overgrown – creating more fuel and intensifying blazes. As West Coast wildfires break records year after year, policymakers have recently paid more attention to the issue and are funding more forest-thinning treatments.

But the 150 million trees that died due to bark beetle infestation during the 2012-2016 drought was a “wake-up call” that the problem of densely packed forests was about more than wildfires, North said. Too many trees relying on limited water can make them more vulnerable to threats like the bark beetles.

“We realized there were too many straws in the ground,” North said, “and that density needed to be way reduced if you’re going to make trees resistant to both wildfire and drought.”

By how much? North’s co-authors used data from a 1911 timber survey of what are now the Stanislaus and Sequoia National Forests to benchmark what they were like before fire suppression policies sent growth into overdrive. The forests of the last century had roughly 20 to 30 trees per acre, with 30-inch trunks, they found. A modern dataset showed that the same areas more recently had about 150-200 trees per acre, with individuals that are about half as big.

The lack of competition in the sparser forests of the past allowed for individual trees to survive and grow, the scientists believe. Those bigger, healthier trees were then able to persist through recurring fires, acute dry spells, insects and disease. Modern-day forest managers should take note, the study suggests.

“There’s a lot of disturbance that one individual has to tolerate before they make it to that size,” said co-author Ryan E. Tompkins, a UC Cooperative Extension forest and natural resources advisor. “We need to start managing for a competition-free environment if we want to maintain these large trees.”

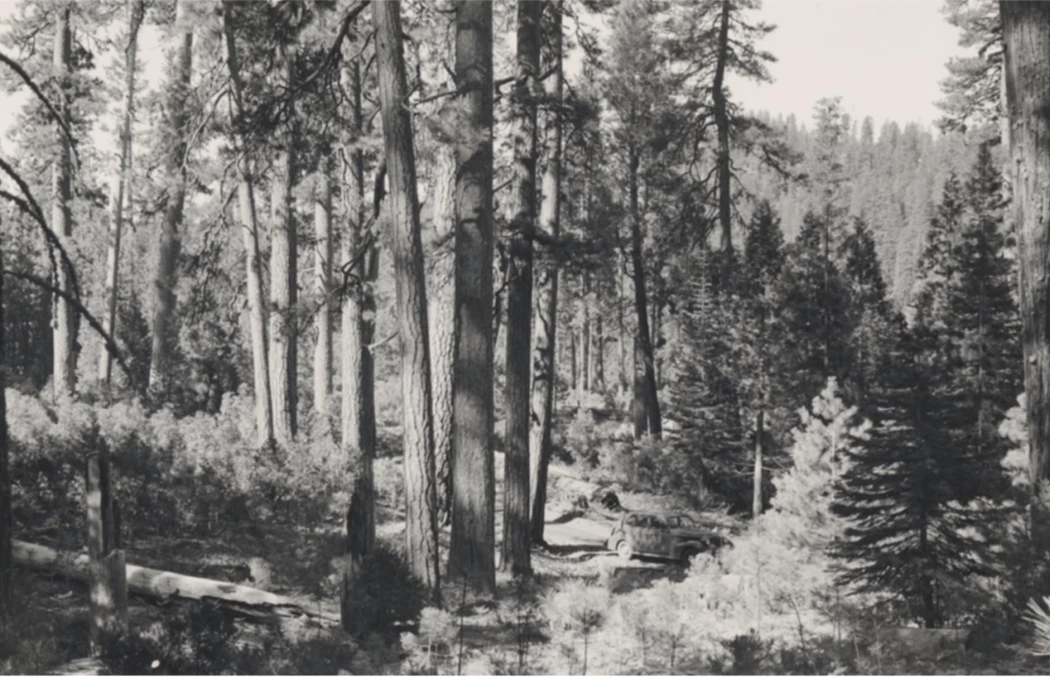

A 1941 photo of Stanislaus National Forest featured in the new study shows “how forest conditions are starting to transition from historical to contemporary conditions,” the authors write, with smaller trees starting to fill in the gaps between clumps of large pines.(Forest Ecology and Management)

A 1941 photo of Stanislaus National Forest featured in the new study shows “how forest conditions are starting to transition from historical to contemporary conditions,” the authors write, with smaller trees starting to fill in the gaps between clumps of large pines.(Forest Ecology and Management)

These are contentious issues in the world of West Coast forestry. While there is broad consensus that thinning is needed, how much and which forests to thin – not to mention how to pay for it — are active areas of debate.

For example, a healthy forest in modern times may not look the same as it did a century ago. CO₂ levels are much higher today and climate conditions are warmer and drier, all factors that affect forest growth, said Christopher Still, a professor of forest ecosystems at Oregon State University who was not involved in the new study. While he found the findings to be credible overall, he said more research would be needed to pinpoint the right thresholds for resiliency.

What’s more, reducing the density of Sierra Nevada forests by 80% would require funding and manpower beyond the hundreds of millions of dollars that leaders like California Governor Gavin Newsom are currently pouring into forest treatments. New processing facilities and commercial applications to handle the extra biomass would be needed on an ongoing basis, North said. It’s unclear how the public would react to logging on such a large scale.

Bill Stewart, a recently retired cooperative extension specialist in forest economics at the University of California, Berkeley who was not involved in the study, argued that dramatic cuts to tree density would mean less carbon sequestration. He said that private landowners such as timber companies have a better track record of keeping trees alive than public agencies like the national forests the new study focuses on.

But for forests to store carbon, they need to survive in the first place, the study authors said, and bigger trees stand a better chance. North and Tompkins have previously led studies on the need to reintroduce the “good fire” that once regularly pared down small trees and shrubs, as well as ones about the planting of trees in naturalistic patches and clumps — rather than tight, straight lines — to help mitigate wildfire damage.

Restoring forests to how they looked before the arrival of European settlers and forestry practices could benefit the long-term survival of not only trees but also the wildlife they shelter and microclimates they create, they said.

“We need to think deeper and restore what made these forests so resilient to stresses in the past,” North said. “Because the future of climate change has a lot more of them in store.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.