Solar Startup Born in a Garage Is Beating China to Cheaper Panels

Labs and well-funded giants had already struggled with this same attempt to ditch silver. Allen remained undeterred and built his own equipment to test one idea after another at a quick clip, until he found a technique that worked. SunDrive Solar, the company he co-founded in 2015 based on this research, proved this week that it has produced one of the most efficient solar cells of all time, according to a leading independent testing laboratory. And SunDrive did so with copper as the metal at the core.

If SunDrive can mass produce its technology — and that’s a big if — the Australian startup could reduce the cost of solar panels and make the industry far less dependent on silver. “The thing about copper is that it’s very abundant and usually about 100 times cheaper than silver,” said Allen, now 32.

SunDrive has raised about $7.5 million to date from Blackbird Ventures and other big-name investors. Mike Cannon-Brookes, one of Australia’s wealthiest people, has backed the startup through his Grok Ventures; so has former Suntech Power Holdings Co. chief Shi Zhengrong, sometimes called the “Sun King” for his outsized role in the solar-panel industry. The company also received more than $2 million via a grant from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, a government body tasked with boosting green technology.

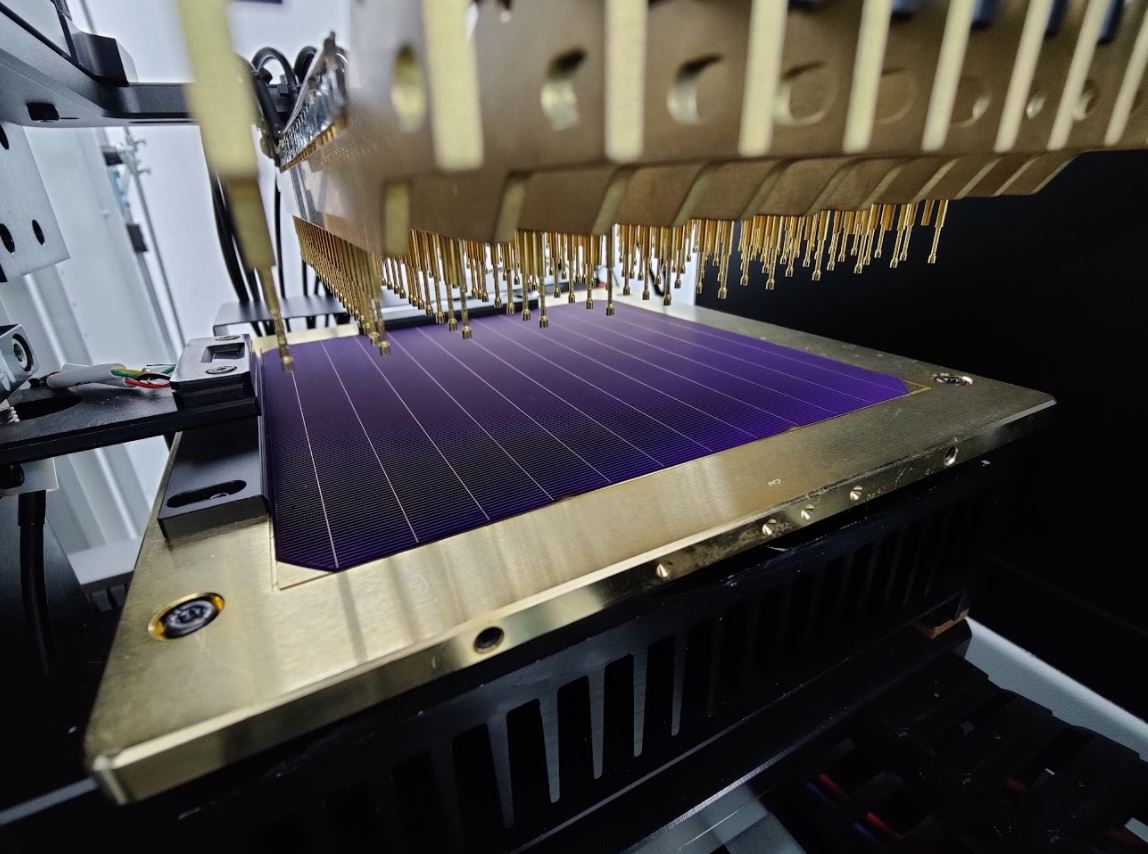

About 95% of solar panels are constructed out of photovoltaic cells made from wafers of silicon. To pull electrical current from the cells, you typically need to fuse them with metal contacts. Silver has long been the metal of choice because it’s easy to work with and very stable. Solar-panel manufacturers rely on a screen printing process similar to that used to place designs on T-shirts, pushing a thick silver paste through a mesh and onto their silicon cells in a fixed pattern. If you’ve ever seen a solar cell up close, the faint, thin lines running across it are the metal electrodes.

Solar panel makers now consume as much as 20% the world’s industrial silver each year. When silver prices are high, the metal alone can account for 15% of a solar cell’s price. Even after a big rally this year, copper trades for a little more than $9,000 a ton in London. That same amount of silver would cost nearly $770,000. The solar industry will need more and more silver as it continues to boom and, at some point, SunDrive's backers believe, it’s likely demand for the metal will constrain the spread of solar electricity needed to bring down greenhouse gas emissions.

The issue preventing solar-panel manufacturers from ditching silver has been that copper doesn’t lend itself to the standard manufacturing techniques, in part because it doesn’t stick well to solar cells. Copper also oxidizes more easily, which impacts its ability to conduct current.

The University of New South Wales has a long history of solar technology breakthroughs, and Allen zeroed in on this copper conundrum as the heart of his graduate studies. Instead of working at the school’s labs, however, Allen thought he could conduct experiments more quickly by building an R&D setup in a garage. He spent a couple years assembling machines that held a liquid copper concoction of his own creation and that could deposit the slurry onto a solar cell in a controlled fashion.

“I always wanted to follow my own curiosity and try out a bunch of random, crazy ideas,” Allen said. “It required some discretion since there were neighbors, and I was walking around in a lab coat with all these chemicals.”

It took hundreds of experiments, but he eventually developed technology that makes it possible to securely adhere thin lines of copper on solar cells. He started SunDrive with his former flatmate, David Hu, 33, in a bid to commercialize the technology. The company now has about a dozen employees. Hu, who grew up in China and moved to Australia at 16, handles the business affairs, while Allen sticks to the science.

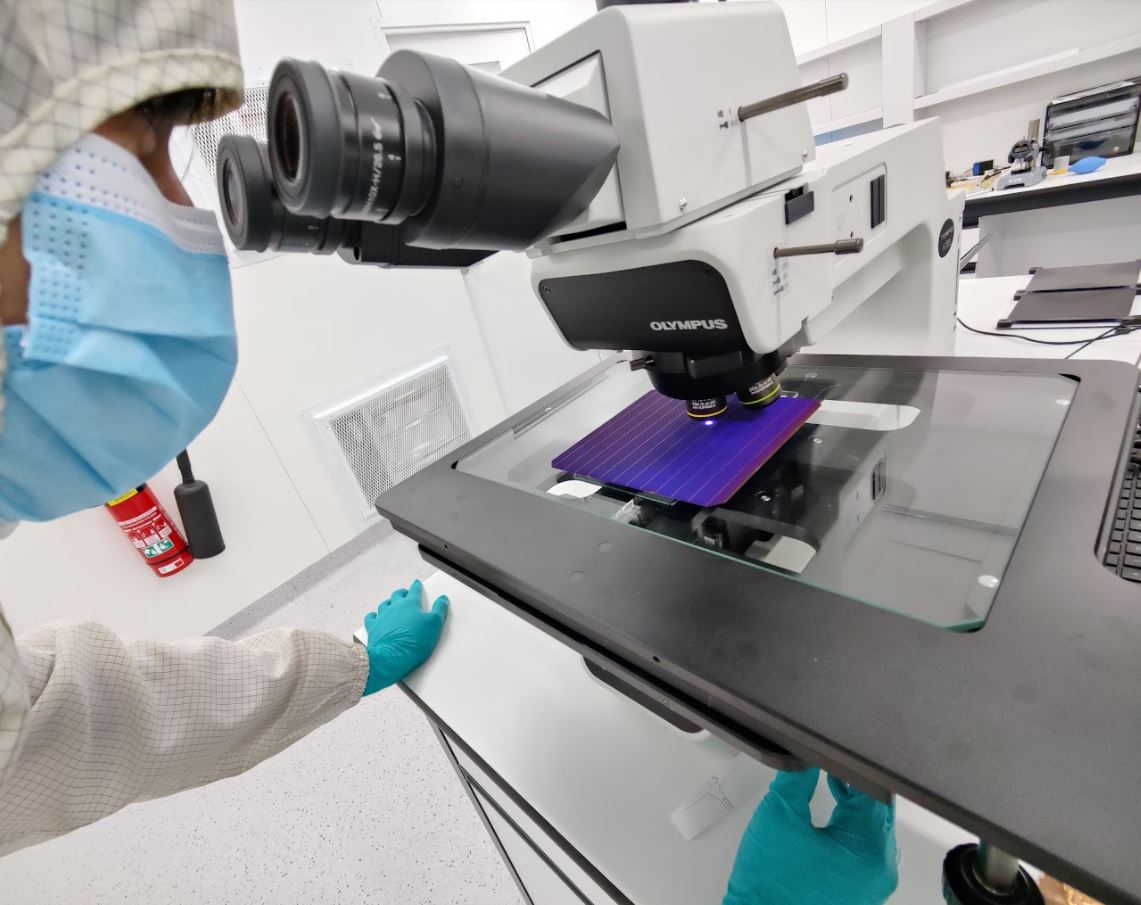

Just this week SunDrive received official word that it had set a record for the efficiency at which its particular design of solar cells convert light to electricity. The result came from analysis by the Institute for Solar Energy Research Hamelin (ISFH), a German organization known for conducing such tests. The efficiency figure — 25.54% — will mean little to people outside of the solar industry. But it’s is one of the key metics by which cells are compared.

Large Chinese solar cell makers have topped the efficiency records for years. Longi Green Energy Technology Co., which sold $8.4 billion of solar technology last year and is one of the world’s biggest manufacturers, held the previous top mark of 25.26%.

Startups in this part of the solar market are rare because of the daunting prospect of competing against giant companies that produce solar cells by the millions at large, expensive factories. Chinese companies dominate, with collective control of the majority of global capacity for the supply chain. “The capital required to a start a new company is huge, and even then it’s not a terribly profitable business,” said Zachary Holman, a professor who studies solar materials at Arizona State University. Still, he said, there are a handful of companies like SunDrive that are aiming for technical breakthroughs that might give them a shot. SunDrive “would need something new like that in order to compete.”

The next step for SunDrive will be proving it can mass produce solar cells reliably and cheaply. “What they have shown so far is high performance on one cell,” Holman said. “They did not show 10,000 high performance cells coming off a several-hour manufacturing run.”

Allen and Hu said they’ve yet to decide on the exact path they will take moving forward. It’s likely that they will try to form a partnership with one or more of the large manufacturers rather than attempting to build an entire solar panel business from scratch. “We might purchase partially complete solar cells and then finish them with our copper process,” Hu said.

Shi, the SunDrive investor nicknamed “Sun King,” said it will be hard to find enough affordable silver if the solar business grows as predicted. Over the next decade, he expects to see manufacturers move to a 50-50 split between silver and copper in the solar cells. “The shift to copper is something that we’ve long desired but has been very hard to do,” he said.

He recalled visiting Allen at his homemade lab and being surprised by what the PhD student had accomplished. “He had all these simple tools and things he’d bought off Amazon,” Shi said. “Innovation really is related to the individual and sometimes the right moment, and not to being at a big company with lots of resources.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.