Saudi Arabia and Russia Go on the Offense at Climate Talks

(Bloomberg) -- After Saudi Arabia announced it planned to reach net-zero emissions by 2060, the instant reaction for many was incredulity and bemusement.

On social media commentators competed to find the best analogies: it’s like an abattoir saying its canteen will only serve vegetarian food, said one. Another quipped it sounded like a tobacco company announcing it’s quitting smoking.

The reality is far more complex. After years of being on the defensive, Saudi Arabia and Russia, the world’s top two oil exporters, have switched to a more active posture in global negotiations to avert climate change. The tactics have changed, but the strategy is the same: protect fossil fuel demand for as long as possible.

By announcing their net-zero pledges, Riyadh and Moscow are attempting to shift the diplomatic narrative, revitalize their influence and secure credibility ahead of a high stakes climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, known as COP26. For years, the OPEC+ leaders tried to slow down the fight against climate change, often questioning the very science behind it. Now, they are presenting themselves as part of the solution, winning a seat at the negotiating table to push their favored climate solutions, analysts and diplomats say.

“This announcement means Saudi Arabia seeks a bigger role in shaping global climate action, keeping oil in the mix for longer,” said Jim Krane, an energy expert at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston.

But the Saudi and Russian net-zero targets go beyond climate. For both nations, climate change negotiations are part of a wider geopolitical bargain. In Riyadh, they offer a rare platform for agreement with Washington, sidestepping other controversial issues where the royal palace and the White House are at odds. For Moscow, it offers a new arena to assert diplomatic muscle as it spars with Europe and the U.S. on issues from gas supply to economic sanctions.

Under United Nations rules, the net-zero targets only apply domestically, so Saudi Arabia and Russia can meet them and continue exporting their oil into the global market unaffected. Yet, if every other country follows through with similar targets, fossil fuel consumption would plunge, undermining the model that sustains their economies.

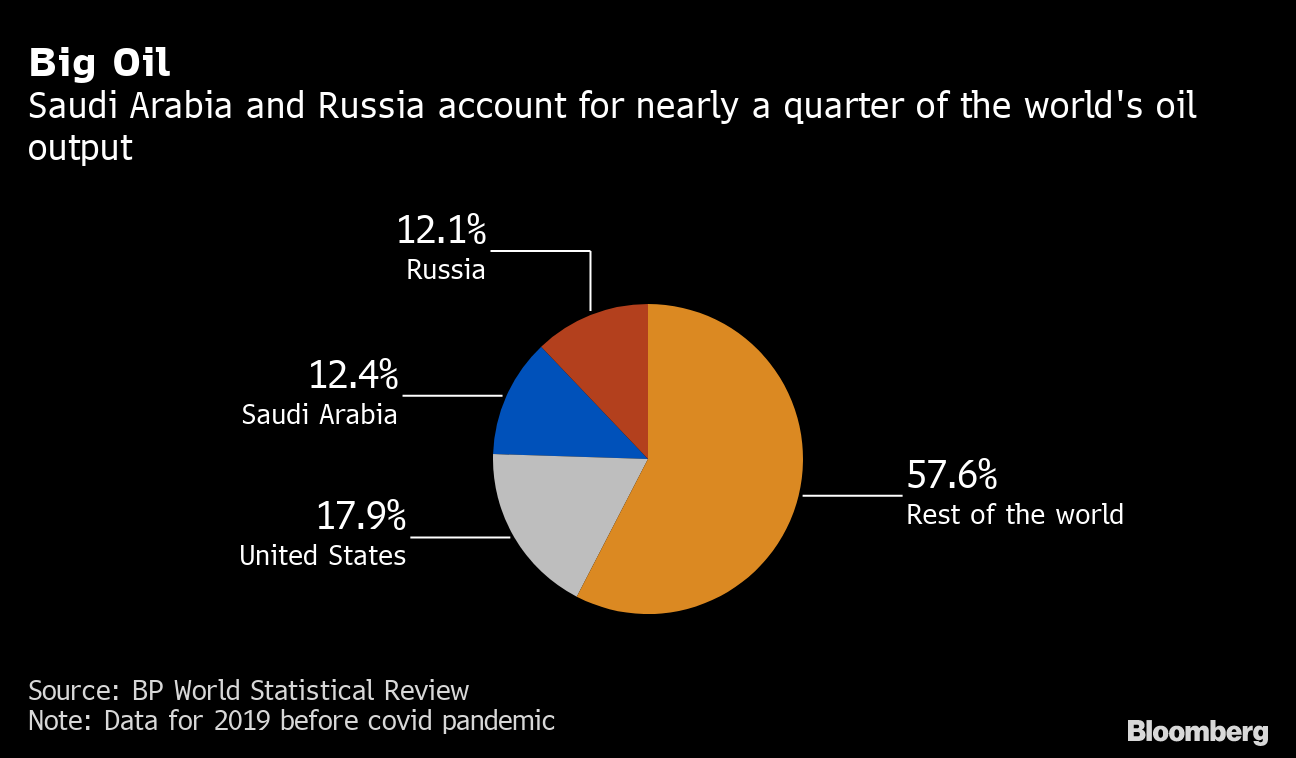

The second best alternative for Saudi Arabia and Russia, which together pump nearly 25% of the world’s oil, is to convince the world it can continue consuming fossil fuels and fight climate change at the same time -- a proposition many climate scientists would says is unrealistic.

“Like the U.S., Russia and the kingdom are energy giants,” said Morgan Bazilian, an energy expert and professor of public policy at the Colorado School of Mines. “All are keeping options as open as possible as they navigate what is likely to be a low carbon future.”

A lot is a stake for both. If the world follows the policies it’s currently implementing, the International Energy Agency believes oil demand could remain above 100 million barrels a day -- close to today’s level -- until 2050. If the world not only delivers its current policies, but also the pledges some countries are making, oil demand may fall to 75 million barrels a day by 2050. And if the world followed a path compatible with keeping global warming to a minimum, oil demand would plunge to less than 50 million barrels a day in 30 years.

In contrast to previous climate change summits, like COP21 that resulted in the Paris Agreement, Riyadh and Moscow feel they have an opening to convince the world that turning against fossil fuels completely would be unwise. Oil, natural gas and coal prices have surged in recent months, in some cases hitting record highs, prompting consumers to fret about energy security. Outside Europe, many nations are worried that fossil fuel supply will decline earlier and faster than demand because of low investment.

Riyadh and Moscow are championing what they call a “circular carbon economy,” in which fossil fuels are burned, but their emissions are captured and either used to produce chemicals and other products or simply buried underground.

The technique, known as carbon capture, utilization, and sequestration (CCUS) is however in its infancy, with only a handful of small commercial projects operating. Both Riyadh and Moscow are also promising to plant million of trees to offset emissions. For its backers, carbon capture and natural offsets like tree planting are pragmatics solution for a world economy still hardwired to oil, natural gas and coal. For its critics, it’s like the promise to fight a blaze with a fire brigade that simply doesn’t exist.

Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman explained the approach after Riyadh unveiled its net-zero target, saying the proposals from oil producing countries like Saudi Arabia need to be given equal footing to everyone else when discussing how to resolve the climate change challenge.

“No one should be too facetious about what tools are in kits that everybody has,” Prince Abdulaziz said. “But if the tools in your kit and mine deliver emissions reductions, that’s the ask and that’s the objective.”

President Vladimir Putin put it more bluntly a few weeks earlier, when he pledged Russia will hit net-zero by 2060: “The climate agenda must not be ‘weaponised’ to promote the economic or political interests of individual countries.”

It’s a view widely shared among OPEC+ countries, which demand what they call an inclusive negotiation during the COP26 summit. “Inclusivity requires that you are open to accept what everybody is going to do as long as he contributes to emissions reduction,” the prince said.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.