In Russia’s Wild East, An Electric Car Proves Cheaper Than a Lada

(Bloomberg) -- When Dmitry Unagaev bought his first electric car five years ago, the purchase bewildered friends and neighbors in his hometown of Khabarovsk. But a lot has changed since then. Today, the city in Russia’s Far East is full of battery-powered autos.

“These cars are almost at every turn,” said Unagaev, 31, who owns an auto service shop. Across the city, the vehicles are parked on the streets and in courtyards. People even hang power sockets from their balconies to charge the vehicles, Unagaev said.

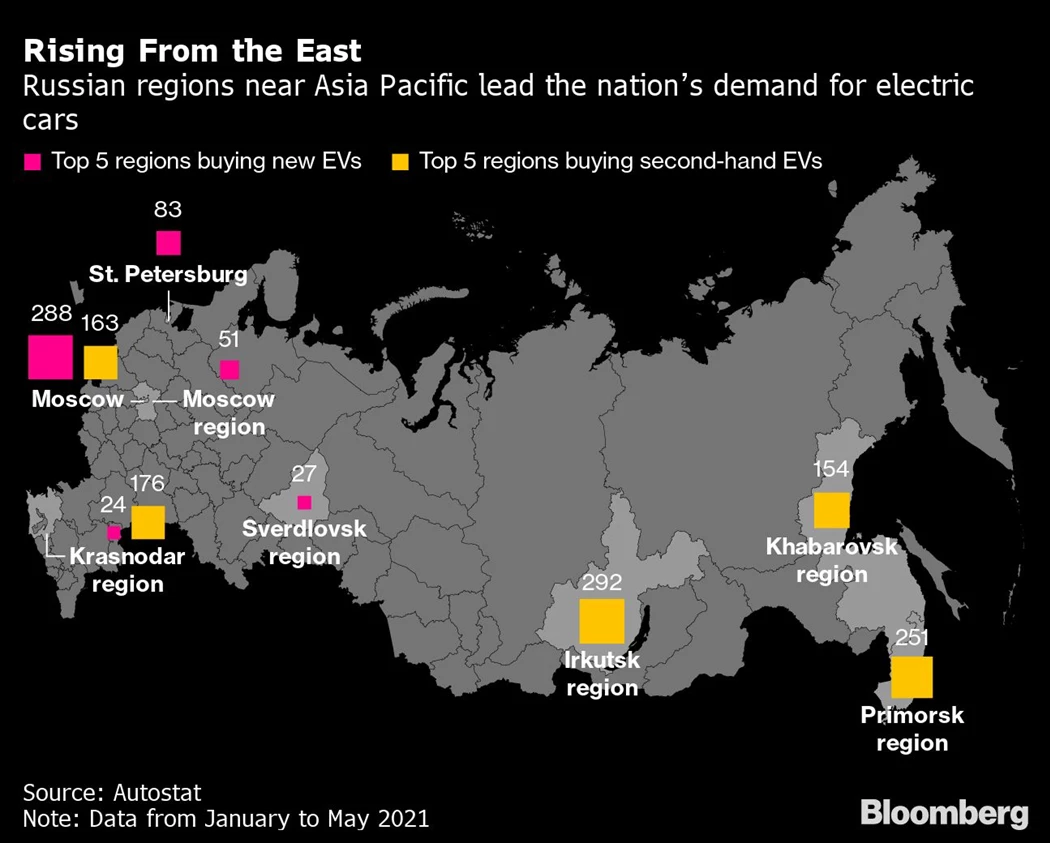

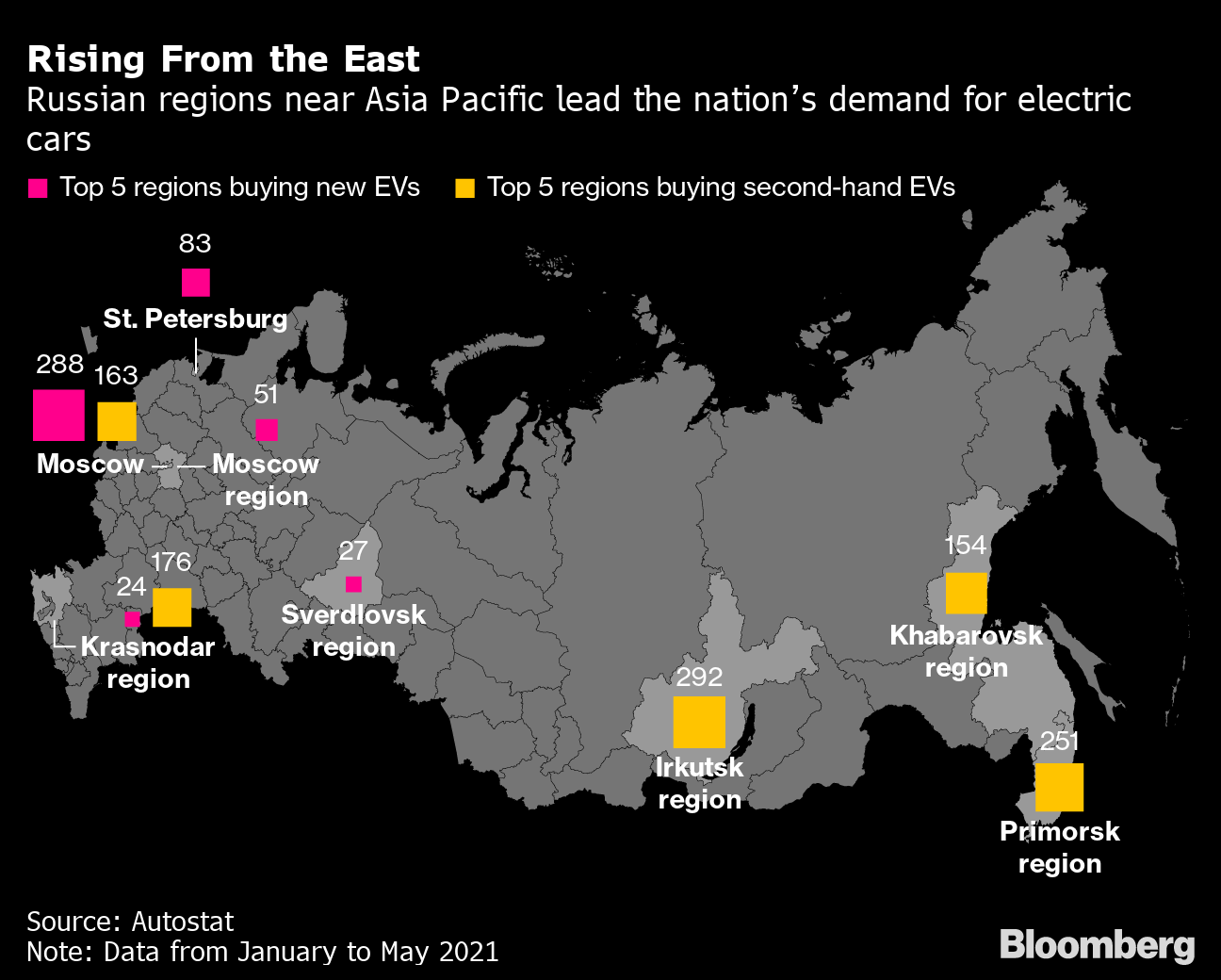

More than a fifth of all electric vehicles imported to Russia between January and May were sold in Khabarovsk and other areas of eastern Russia — even though the region claims just 4% of the nation’s population, according to data from the Moscow-based analytical agency Autostat. The country’s capital, home to at least twice as many people, accounted for just 14% of EV sales.

Russia’s so-called Far East isn’t particularly wealthy, nor is it a bastion of environmental awareness. Its embrace of electric cars stems from the unique economics of a region that’s isolated by its sheer distance from the country’s west. Even so, the region offers a glimpse of the trends — more expensive oil, cheaper power, and falling EV ownership costs — that someday could drive widespread adoption of electric models throughout the country and beyond.

With Asia literally next door, the locals have easy access to cut-price used electric cars imported from Japan. Unagaev’s first battery-powered vehicle was a used Nissan Leaf. Models from 2011 to 2013 typically cost from 400,000-600,000 rubles ($5,500- 8,200), according to ads on a popular car website in Russia. Unagaev eventually upgraded from the Leaf to a second-hand Tesla.

Russia’s Far East also enjoys low-cost electricity, which is subsidized to stimulate economic development in the region. At the same time, due to insufficient local refinery capacity, fuel prices are typically higher than the Russian average — a premium of 6% as of late July, according to the Federal Statistics Service.

The combined market forces are achieving something in this corner of Russia that government policies and technological advances hope to bring about in the rest of the world — making battery-powered cars more affordable than their gas-powered counterparts.

“The main driver is the same all over the world,” said Eugene Tyrtov, senior consultant at Moscow-based Vygon Consulting. “Consumers massively begin to vote with their rubles, euros and dollars for electric cars as soon as they become more economical than traditional cars.”

The math is simple, said Olga Ivanova, 41, the head of a construction firm in Irkutsk in eastern Siberia. She pays about 500 rubles monthly ($7) for electricity to charge her used EV. Gasoline for her family’s second car costs almost 10,000 rubles a month.

“We calculated, with my husband, that we could save some 200,000 rubles a year” on fuel and the other costs of owning a gasoline car, Ivanova said. “I can’t say that I need money, but when you understand that you can get the same comfort, the same joy and save 200,000 rubles, that’s quite pleasant.”

The average savings from a used Nissan Leaf in Russia’s Far East is about 40,000-50,000 rubles a year, according to Vygon Consulting, compared with the cost of driving a domestically-produced Lada Granta, popularly referred to as the “people’s car.” That’s close to a typical monthly regional salary.

“We also have a gasoline car, but don’t use it a lot as we don’t need to drive large distances,” said Alexey Zhukov, a 28-year-old marketing specialist in Khabarovsk. He bought a used Nissan Leaf earlier this year, following in the footsteps of some relatives.

This microcosm in Russia’s Far East is distinct from the reality in the rest of country. Electric vehicles account for less than 0.2% of the nation’s total passenger-car fleet, according to Vygon. Not surprisingly, the high purchase price of a new EV remains the key obstacle for prospective buyers. That should shift as the cost of EVs — driven by declines in battery prices — drops. The volume-weighted average price for a lithium-ion battery pack was $137 per kilowatt-hour in 2020, down from $1,191/kWh in 2010, according to data from BloombergNEF. And prices will continue to fall, getting below $100/kWh by 2024, a key benchmark for parity with combustion engines, and hitting about $58/kWh in 2030, according to BNEF senior analyst Aleksandra O’Donovan.

“We see EVs costing as much as traditional cars or even less in the late 2020s,” O’Donovan said.

External factors such as the cost of electricity compared with gasoline will depend on government policies, subsidies or carbon markets, which vary greatly in scope and ambition from one country to the next. Still, the proliferation of electric cars, even in small pockets like Khabarovsk, widens exposure to the advantages of the technology that go beyond cost and carbon emissions.

“The dynamics of an electric car, the way it accelerates,” is a bonus on top of the money saved, said Ivanova. “It’s an incomparable feeling.”

Stacy Noblet, a senior director of transportation electrification at ICF, a consultancy in Washington, D.C., said the appeal to consumers will only grow. “EV drivers are sharing their own stories and telling their neighbors,” she said.

Word-of-mouth buzz is gaining momentum throughout Russia. Across online forums, electric-car enthusiasts are spreading the word, doing their best to convince their fellow citizens of the benefits of “passing by gas stations smiling.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.