Coal’s Grip on Asia Strengthens as Early Phaseout Bids Stall

(Bloomberg) -- Coal’s future in Asia is looking brighter, as the top-consuming region’s efforts to shift to cleaner energy suffer a series of setbacks.

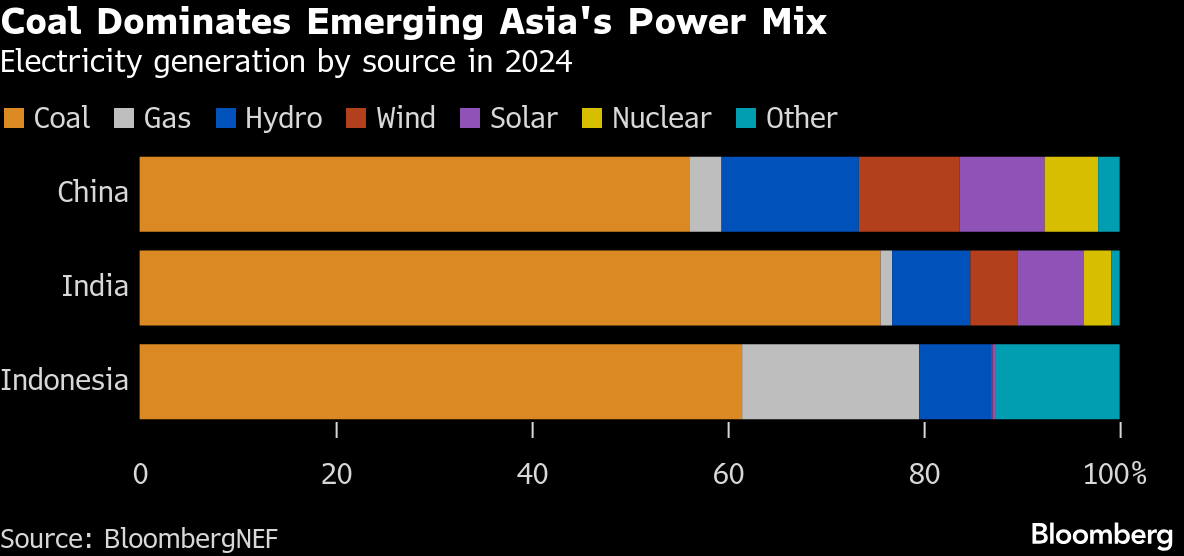

Indonesia has canceled a flagship project that was the poster child for shuttering coal plants early. India is considering expanding its fleet until mid-century instead of through 2035. And China’s on track for another year of record mine output, bolstered by demand from the chemicals sector, despite a steady roll-out of renewables.

The through line here is that concerns over energy security and costs are trumping the climate agenda in Asia’s high-growth, high-polluting economies. Power demand is soaring for everything from air conditioning to AI data centers, and governments keen to avoid outages are waving through coal plant approvals.

“It comes down to supply security and cost,” said Jom Madan, a principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “Even with record wind and solar buildouts, new additions are still not keeping pace with the massive increase in power demand from population growth, rising incomes and now the surge in data center capacity.” That gap is filled by fossil fuels like coal and gas, he said.

Asia’s push for coal reflects a global reality. At the United Nations’ COP30 climate summit in November, almost 200 nations signed an agreement that avoided an explicit mention of transitioning away from fossil fuels, as developing countries argued for economic growth using all energy sources.

China, which mines and burns more than half the world’s coal, has given additional support to the fuel it calls its “ballast stone” since a series of power shortages in 2021 and 2022. Since then, production, imports and consumption have all soared to record levels.

The country is expected to add 80 gigawatts of new coal capacity in 2025, the highest level in a decade, with similar amounts expected to come online in 2026 and 2027, according to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Chinese firms are also investing tens of billions of dollars in new coal-to-chemical plants to help reduce reliance on imported oil and plastics.

India’s total coal-fired capacity could rise 87% to reach 420 gigawatts by 2047, according to people familiar with the matter, a much longer runway for additions than current projections to cap them by 2035. In Indonesia, the world’s largest thermal coal exporter, coal power capacity more than doubled in the decade to 2024. The build-out is set to continue under President Prabowo Subianto despite his ambition to fully transition to renewables by 2035.

Together, these three countries are responsible for the largest increase in carbon emissions and coal-fired power generation since the 2015 Paris climate agreement, according to CREA. Without them, global energy sector emissions would already have begun to decline before 2020, the think tank said.

The region has struggled to wean itself off a fossil fuel that remains a cost-competitive source of stable power thanks to its abundance, and because of the need to pair clean energy sources with batteries and robust grids. Asia’s fleet of 2,000 coal plants is also decades younger than that of Europe and the US, and retiring it early requires financial support to end power-purchase agreements.

“There’s a lot higher degree of pragmatism and realism today relative to, let’s say 10 years ago,” said Leslie Maasdorp, chief executive officer of British International Investment Plc, the UK’s development finance institution.

“It’s not a simple exercise of closing coal, and building renewables” and governments are now looking into the finer details, he said during a briefing in Singapore on Tuesday.

Countries like Indonesia had hoped that initiatives such as the $20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership would help them shift away from coal. But the G7-funded deal has only brought in $3 billion so far, and a proposal to shut down its flagship project Cirebon-1 in West Java seven years early was scrapped last week. The cancellation comes after the US also pulled out of the climate assistance program under President Donald Trump’s pivot back to fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, Singapore-backed “transition credits” have yet to attract commitments from governments or companies to pay for the early shutdown of a coal plant in the Philippines while offsetting their own pollution. Their concerns revolve around real emissions savings, job losses, and scalability of the model.

Still, “closing the first market-leading coal-to-clean transaction in 2026 remains a core objective,” said Joseph Curtin, vice president for energy transitions at The Rockefeller Foundation, which is among the organizations spearheading the effort.

Coal’s dominance in Asia’s power sector is not guaranteed to continue, especially amid rapid renewables installations and falling storage costs in China and India.

Even as China adds new coal plants, total generation has fallen this year. If India and Indonesia follow through with their renewable targets, that could lead to power-sector emissions peaks by the end of the decade, according to CREA.

“As renewable energy and storage costs reach record lows, investments in new coal will only get harder to justify,” said CREA co-founder Lauri Myllyvirta.

In the meantime, Asia — home to some of the world’s biggest populations and fastest-growing economies — remains reluctant to quit coal for fear of power shortages that could hurt development and public sentiment.

“Retiring a plant early is just not realistic” in the region’s price-sensitive markets, said Wood Mackenzie’s Madan.

(Updates with BII’s comments in 11th and 12th paragraphs.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.