Markets Bet Inflation Is Hot Enough to Spur Reluctant Rate Hikes

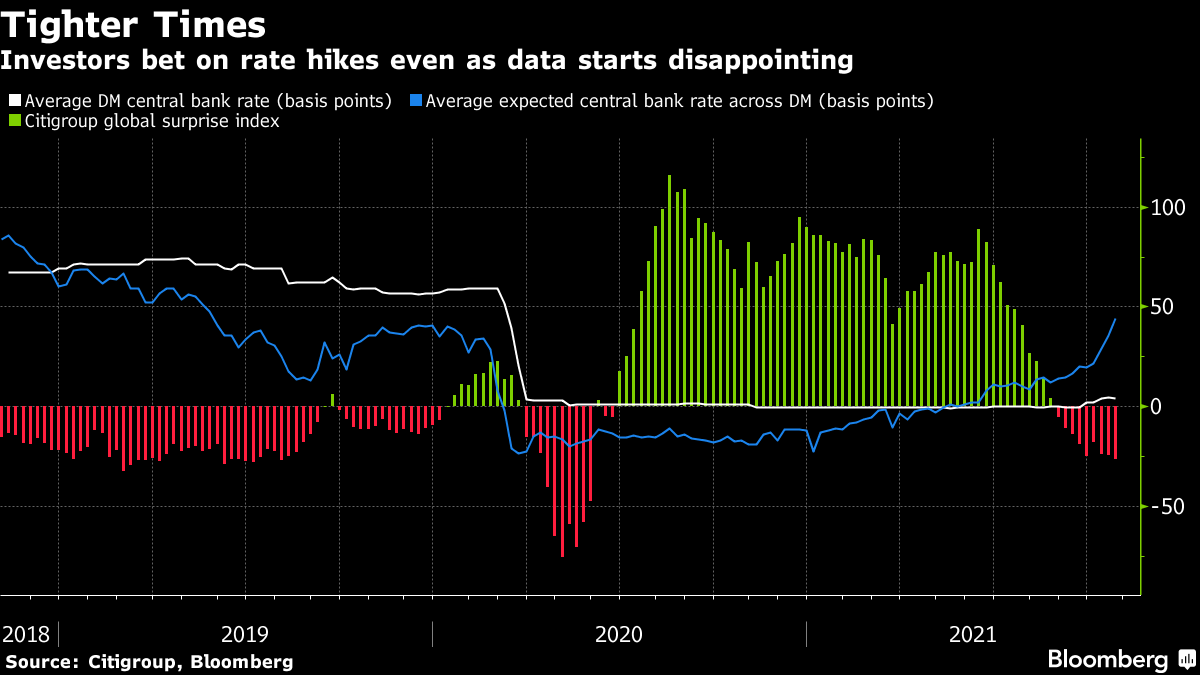

(Bloomberg) -- Investors are stepping up bets that the world’s key central banks will raise interest rates sooner than they’d planned, and faster than they’d like.

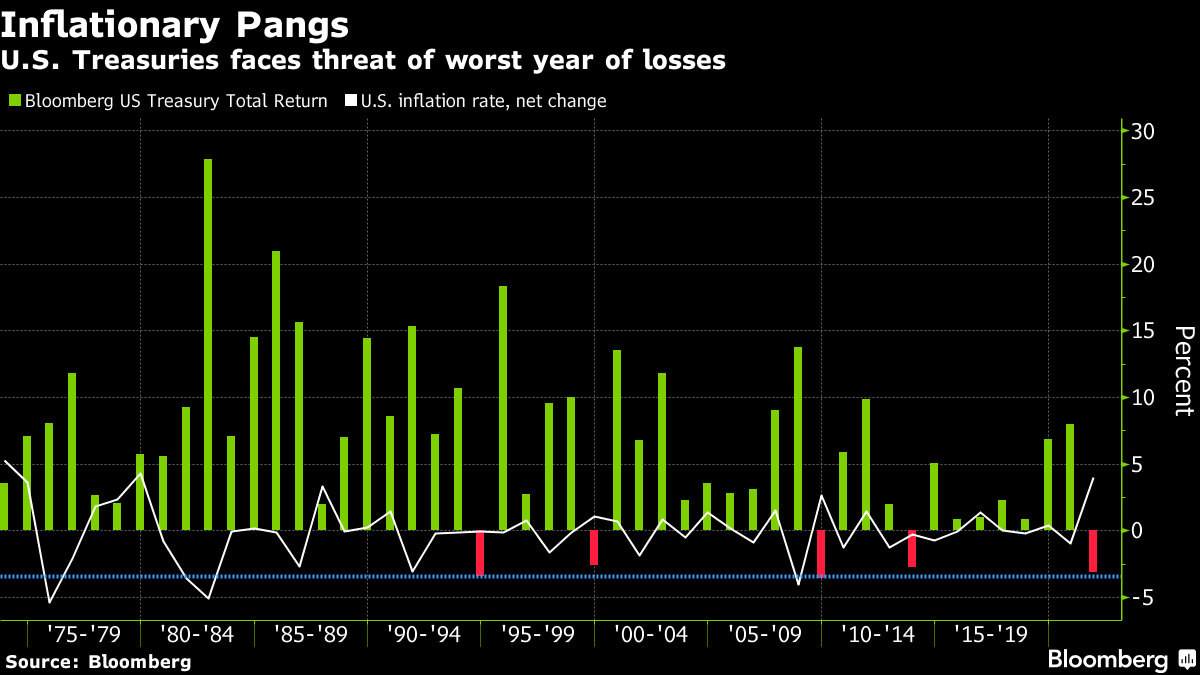

Global bonds are headed for their worst year since 2005, according to a Bloomberg index, with traders seeing rate hikes in the pipeline across developed economies.

That’s because they think central bankers, who’ve been counseling patience ever since Covid-19 arrived, are changing course. Policy makers now sound more worried that pandemic inflation will stick around -- and more willing to boost borrowing costs in order to stamp it out.

Nowhere has the pivot been sharper than at the Bank of England, where five words from Governor Andrew Bailey last weekend -- “we will have to act” -- were enough to drive the latest leg of the tightening trade. Just a few weeks ago, Bailey was saying the “hard yards” for the economy were still to come.

Markets now anticipate a BoE hike as early as next month -- and they reckon the turn away from cheap money is gathering pace in other countries too.

Tighter Fed?

Investors are pricing half a percentage point of Federal Reserve rate increases by the end of 2022, and they expect some developed-economy peers to have hiked multiple times by then.

That’s not the outlook that central bankers have generally been projecting in the past 18 months. Instead they’ve argued that pandemic inflation will soon ease, and interest rates should stay low to help growth and hiring recover -- a case made by some investors too.

“If the Fed were to hike too quickly” then “they could suddenly realize that global demand has vanished and then domestic growth would slow accordingly,” said Peter Chatwell, head of multi-asset strategy at Mizuho International Plc. “We’d say a Fed hike in the fourth quarter of 2022 would be premature.”

But the rhetoric from policy makers has shifted because more and more key indicators -– from oil markets and shipping conditions to consumer and employment surveys –- suggest price pressures will persist.

With inflation already above-target almost everywhere, that’s a prospect that even today’s more dovish central banks are signaling they won’t ignore.

‘More Aggressive’

“The next several months are critical for assessing whether the high inflation numbers we have seen are transitory,” Fed Governor Christopher Waller said on Tuesday. “If monthly prints of inflation continue to run high through the remainder of this year, a more aggressive policy response than just tapering may well be warranted in 2022.”

Current wagers for the first Fed hike center on July or September next year, and some think it could even come sooner. Last month officials were evenly split on whether they should act next year or wait until 2023. Back in March, liftoff wasn’t expected until 2024.

Treasuries are being swept up in the selloff, delivering a 3.1% loss this year through Oct. 20, according to a Bloomberg index. That’s not far off 2009’s record 3.6% annual decline. The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield has risen more than half a percentage point since early August, to almost 1.7%. A bond-market gauge of 5-year inflation expectations rose above 2.9% Thursday, the highest in more than a decade. “The Fed seems to be teeing up for the possibility of some sort of rate hikes, or keeping that option open, during the second half of next year,” says Subadra Rajappa, the head of U.S. rates strategy at Societe Generale. That “might be enough to quell some of the fears in the market of the Fed not having control on inflation.”

In some places, investors see central banks moving faster still.

Traders in Canada reckon its central bank will raise rates early next year and continue hiking, even though Governor Tiff Macklem says he won’t budge until slack in the economy is absorbed and inflation returns sustainably to its target range. The bank has said it doesn’t expect those conditions to be met before the second half of 2022.

New Zealand has been the most hawkish of the lot, halting bond purchases in July and then raising rates despite a surge in the pandemic as the delta variant shattered the country’s Covid-zero plans. RBNZ Governor Adrian Orr is expected to increase the official cash rate again next month.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has been one of the most dovish of the major central banks, but economists and investors increasingly doubt it can hold that line, and they’re tipping it to move even before the Fed. Governor Philip Lowe insists he doesn’t expect to raise rates until 2024 at the earliest -- he sniped last month at markets for misguidedly betting on a hike next year.

Europe Too?

Even the euro area -- which hasn’t seen an interest-rate increase for more than a decade -- might get one next year, investors now speculate. They only pricing in a small adjustment, which would keep the European Central Bank’s benchmark deposit facility rate well below zero. Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau warned markets not to expect even that much. “There is no reason for the ECB to raise its interest rates next year,” he said on Tuesday, because inflation will likely be back below the 2% target by the end of 2022. Give or take a few months and a few basis points, that’s essentially how many central bankers in the advanced economies still see things.

They assume inflation will ease as the supply side of economies returns to normal and even then it should be allowed to run above forecast to let economies and labor markets heal. They may also be hoping that by talking tough, inflation expectations will retreat without the need for hikes.

‘I Do Worry’

Plenty of investors say this approach underestimates the risks. “I do worry -- and more and more people in the markets seem to as well -- that there could be a surprise on the sustained side with inflation,” says Jack Malvey, a bond-market veteran and former chief global fixed-income strategist at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc, who’s now a counselor at the Center for Financial Stability.

What’s more, with rates at or near zero across the developed world, there’s not much of an option for investors to bet in the opposite direction -– making the rate-hike trade hard to resist.

Still, investors mostly aren’t pushing the central banks too hard, at least not yet.

Kathy Jones, chief fixed-income strategist at Charles Schwab & Co., says a U.S. hike next year wouldn’t be surprising –- but she sees no cause for the Fed to rush. “I remember when the market really did dictate what the Fed had to do, because inflation was so high and there were so many concerns,” says Jones. “This is nowhere close to that.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.