The Two Minutes That Made Traders Lose Faith in the Gas Market

(Bloomberg) -- More than a week after an extreme bout of volatility roiled the US natural gas market, traders are still fuming over a glitch they say sowed chaos in a key commodity market.

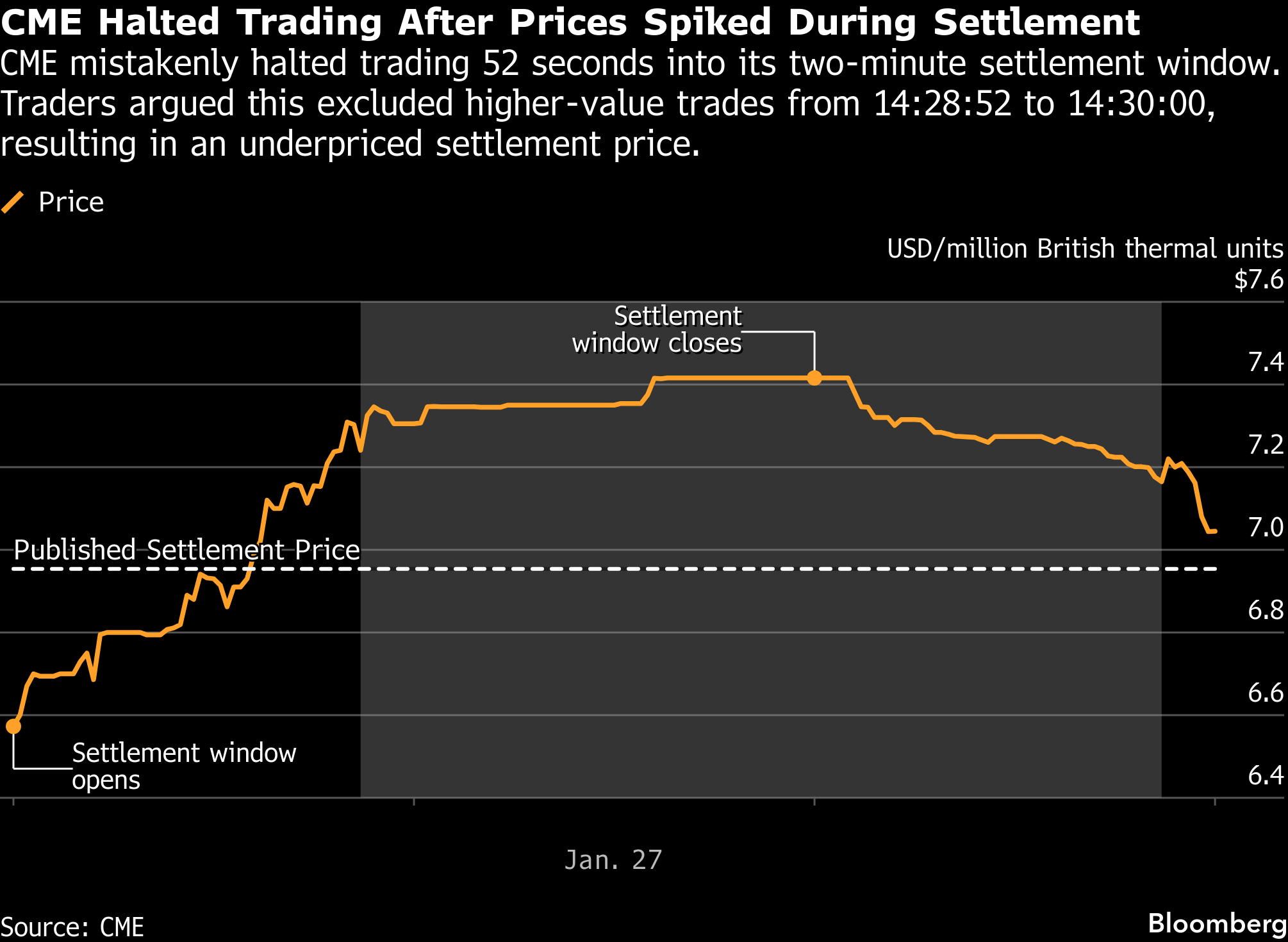

During a record-breaking surge in gas futures on Jan. 27, the New York Mercantile Exchange imposed an extraordinary 2-minute trading halt during the market close that skewed the settlement price and confounded traders already exercised over a demand outlook that had been upended by cold weather. The market pause, which should have lasted only five seconds, was the ninth circuit breaker triggered in the past day.

"Something clearly did not operate the way that it should have that day and it is highly likely it impacted the day’s economics," George Cultraro, Head of Global Commodities Trading at Bank of America said in an interview.

For some investors the incident meant losses, while others were left with concern about the integrity of the market, according to interviews with 10 traders.

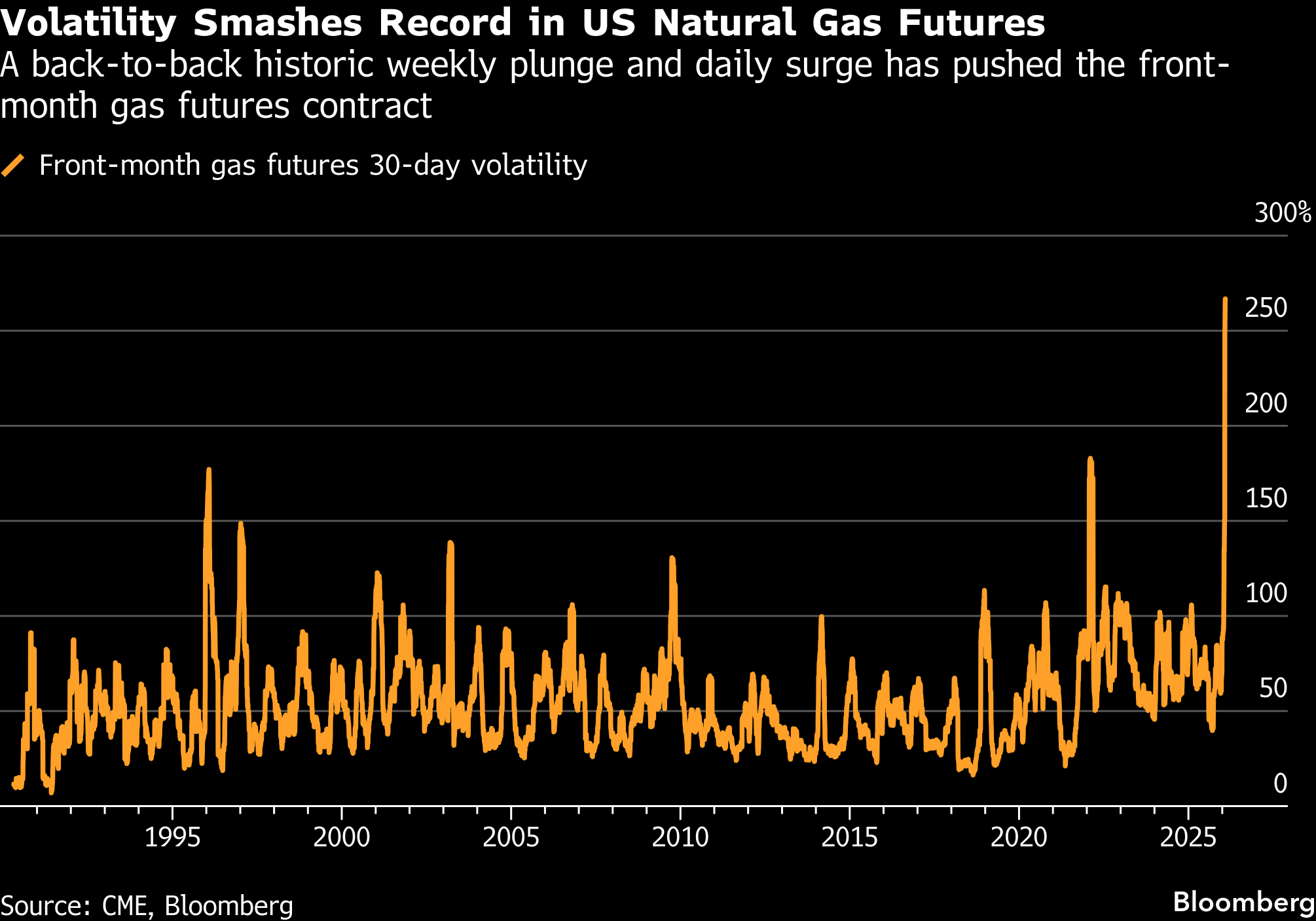

The CME Group Inc., which owns Nymex, informed traders that a “technical error” had caused the circuit breaker to last longer than the usual five seconds. But for many investors, the incident was emblematic of a market plagued with issues. Natural gas has grown extremely volatile as US liquefied natural gas exports and the artificial intelligence boom supercharge demand. Futures prices had surged 119% during Jan. 20-26, a 35-year record for the period, before logging the biggest single-day crash on a percentage basis in 30 years the following week.

Now, investors are demanding answers from CME, as well as from regulators. What caused the glitch? What recourse do they have to recoup losses? And haven’t the powers-that-be noticed that pervasive illiquidity heading into contract expiration can cause wild price swings that short-circuit the exchange’s market mechanism?

CME said in a statement that it has addressed the technical issue behind the circuit breaker but declined to comment on the reasons for the malfunction, or its impact on investors. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission said that market moves, and thus the circuit breakers, appeared to be “consistent with recent supply and demand fluctuation.” The agency added that it’s “continuing to evaluate related trading activity.”

Lottery Ticket Losses

The chaos stemming from the mishap rippled beyond gas futures. In the options market leading up to that day, tens of thousands of “lottery- ticket” bets had been placed on gas ending the day above $7 per British thermal units. If those positions remained open and had settled at $7.20 (as suggested by the bids and offers during the halt,) the play could have yielded a $40 million jackpot for a bet that in mid-January was nearly worthless.

The window for a win was extremely narrow but, heading into the close, odds were good. Prices had crashed through the $7 level and then furiously rallied to $7.31 with 68 seconds to go before the end of the settlement period. Then came the circuit breaker. Though investors were flying blind, bids and offers continued to stream in which, if executed, would have driven the price to $7.40, according to traders. But because the trading halt lasted so long – only lifting after the market close – those transactions weren’t fulfilled. The settlement price posted at $6.95, rendering the lottery ticket options worthless.

CME declined to share data on how many positions remained open at the close.

“The exchange having a pause during options expiry was quite absurd,” said Bill Perkins, founder of Skylar Capital. “That caused a lot of issues for market participants which are still being worked through.”

At least one investor caught out by the incident — and who asked not to be named discussing private matters — complained to CME and said the agency advised filing a complaint to seek recovery of losses. But because it would be difficult to prove what would have happened during those two minutes had trading not frozen, the investor said recouping anything would be unlikely.

‘Banging the Close’

While the errant circuit breaker was a key disruptor on Jan. 27, the frequency of the halts point to another issue with the market: pervasively low liquidity as contracts near expiration.

When a market is illiquid, virtually any activity can touch off outsized price moves. And when those swings are concentrated during the settlement window, they can move other markets in unpredictable ways.

"Natural gas futures are far more than a mere financial instrument,” said Adam Sinn, CEO of hedge fund Aspire Commodities. “They are a physical product that benchmark pricing for natural gas consumers, as well as setting the monthly electricity contract prices which determines Americans’ energy bills. The importance of the settlement being a legitimate process cannot be understated.”

In any energy market, liquidity tends to decline heading into expiry as traders roll from one contract to the next. But traders say that, in gas, regulatory caps on the number of contracts a trader can hold are particularly hampering. Although the size of the market has ballooned, so-called position limits constrain participation because smaller traders often can’t meet the requirements. That gives large, well-capitalized speculators, like hedge funds, an outsized influence on market moves when liquidity dries up.

The irony is that, while the position limits in CME are meant to guard against malfeasance, illiquidity can facilitate a type of manipulation called “banging the close,” in which a party concentrates a large volume of their trades during the settlement window to move the closing price in a particular direction. Aspire’s Sinn said this could be one explanation for gas’s moves on Jan. 27.

“CFTC limits are arbitrarily reducing liquidity and that creates more volatility,” Perkins said. “To fix the liquidity issue we need to get rid of limits entirely or at least revise them."

At the same time, Intercontinental Exchange, called ICE, has become the platform of choice for physical US gas traders. The spread between prices on ICE and CME has widened – swelling last week to the biggest differential on record, according to traders. The widening spread would affect money managers and producers that use Nymex futures to hedge against price fluctuations, potentially resulting in losses, four traders said.

Not a One-Off

The market was already primed for chaos in the days leading up to Jan. 27, as forecasts abruptly shifted from milder-than-normal weather to a deep freeze across much of the country. That sent futures surging. As the cold knocked out gas production, prices rose even higher. That it all occurred as traders were rolling from the February contract to March only exacerbated the swings.

It could all happen again, warned Perkins. Barring any changes to how the market operates, another cold snap could trigger a similar explosion at settlement.

“A great deal of market participants have not seen price volatility like this since the 2014 winter and its extreme gyrations,” said Campbell Faulkner, senior vice president at brokerage BGC Group Inc. “All of this has combined to create an environment that has reminded people of the danger and difficulty of trading natural gas."

©2026 Bloomberg L.P.