Mexico Sees a Future in Shale Gas. Just Don’t Call it Fracking

(Bloomberg) -- In the swampy lowlands of Mexico’s Gulf Coast, Petroleos Mexicanos is pumping high-pressure jets of water, chemicals and sand into the ground to crack open natural gas-soaked rocks that are so hard they don’t yield to traditional drilling.

In most of the world, the technique is calling fracking. But in Mexico, where the practice is still deeply controversial, Pemex has a different name for it: “stimulation of complex geological deposits.”

Whatever it’s called, Pemex has been quietly doing it in Veracruz, Nuevo Leon and other states across Mexico for at least a decade. Now, Pemex executives are evaluating how it can extend its use to the nation’s mostly untapped shale fields, with the aim of reviving production and the struggling state driller, all while weaning the nation off of US gas.

“What you know of as fracking is very different today, we are not going to do that,” Pemex Chief Executive Officer Victor Rodriguez told lawmakers in August. “But the potential is there. So what are we going to do? Leave it in the ground, continue drilling the fields we have, and remain dependent on the US for gas?”

Pemex and the Mexican government, which tried to constitutionally ban the practice under former President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, have demurred on acknowledging that the company engages in fracking in part because of intense push-back from environmental and community groups in recent years.

The practice has already contributed to groundwater contamination and earthquakes, according to US government environmental researchers and Texas’ main oil-industry regulator. In the tiny pueblo of Los Ramones in Nuevo Leon State, locals sounded the alarm after tremors and water shortages began to affect their community, according to a recent report from the international Commission on Environmental Cooperation.

“They’re not calling it what it is because they know it wouldn’t be well-received politically,” said Alejandra Jimenez, an activist at the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking. “Everything points to the fact that the government is going to do more fracking, and at the end of the day, it’s a continuation of what they’re already doing.”

A Pemex spokesman didn’t respond to requests for comment. Mexico’s energy ministry also didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Whether it’s called hydraulic fracturing, well stimulation or something else, the government’s acknowledgment that it’s considering more of it is a sharp reversal for President Claudia Sheinbaum, an environmental engineer who disowned the practice during her campaign. The legacy of AMLO’s staunch opposition to it also likely contributed to the government’s hesitation to call it fracking, even as Pemex increasingly leans into the technique to quell a slide in crude and gas production.

If it all sounds like history repeating itself, that’s because it is. A 2013 oil reform by then-President Enrique Pena Nieto stoked a wave of optimism over Mexican shale, until AMLO slammed the door on most foreign investment in the energy sector.

For Pemex, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The company is flailing under a $100 billion-plus debt load and output has slumped to a 15-year low. The company raised some funds from investors to pay short-term debts, including the roughly $20 billion it owes its service providers, and is offering to buy back $10 billion of its global bonds. But it’s unclear whether the plan will meaningfully turn production around. It’s refineries are bleeding cash and the company has suffered a spate of explosions, accidents, oil spills and fires in recent years that prompted many investors to flee.

Modern fracking techniques were developed at the end of the last century to harvest gas and oil from shale and other types of ultra-hard rock that had evaded all previous attempts at penetration by petroleum engineers. The practice involves pumping cocktails of water, chemicals and sand into a well to pummel the surrounding rocks and create millions of microscopic fissures through which gas and crude can flow into the well and up to the surface.

Fracking is different from other specialized oilfield techniques such as enhanced oil recovery, which involves pumping carbon dioxide or water into wells to scrape remnant crude from the bottom of aging fields and push it to a separate array of wells on the other side of the field.

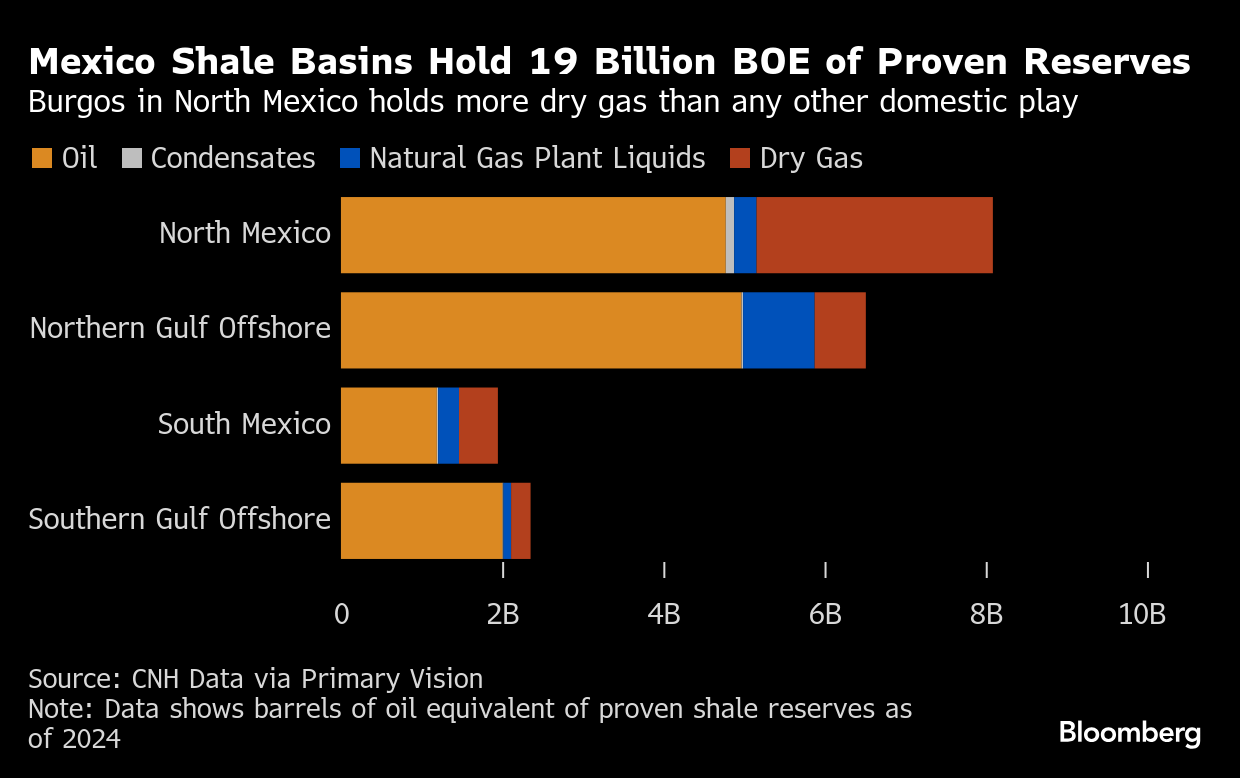

A recently published comprehensive business plan aims, among other things, to tap Mexico’s estimated 545 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas resources, the sixth largest reserve in the world. Over 60% of that trove, along with some 6.3 billion barrels of tight oil, are located in the Burgos Basin, an extension of Texas’ Eagle Ford play just over the US-Mexico border.

Pemex’s new plan comes as some of the biggest US operators are beginning to question the future growth potential of US shale. Diamondback Energy, the biggest independent oil producer in the Permian Basin, has said it already believes US crude production has peaked this year and will decline in the months ahead.

Mexico’s Agua Nueva formation, like Texas’ Eagle Ford field, is a layer of rock containing organic matter from the late Cretaceous Period that has the potential to provide as much as 2.5 billion cubic feet of gas per day, according to Wood Mackenzie.

That formation alone could help Pemex reach its goal of lifting gas output by almost one-third by 2030. The company estimates it can increase daily gas output by 500 million cubic feet, in addition to 300,000 barrels of oil, from unconventional deposits, according to the document.

Ramping up domestic gas production is all the more crucial for Mexico as it seeks to wean itself off a reliance on Texas supplies of the fuel. Mexico imported 7.3 billion cubic feet of gas daily via pipeline from the US in May, a record high. Amid heightened tensions with the Trump administration over everything from trade to security and immigration, gas flows could become a flash point if talks turn sour.

“If the US turns off the tap, Mexico goes dark,” Pemex’s Rodriguez said, calling domestic gas production a matter of national security.

Increasingly, severe weather is also a threat to Mexican gas flows. In February 2021, one ancillary impact of the deadly winter storm that descended on Texas was the interruption of gas shipments across the border as pipelines froze.

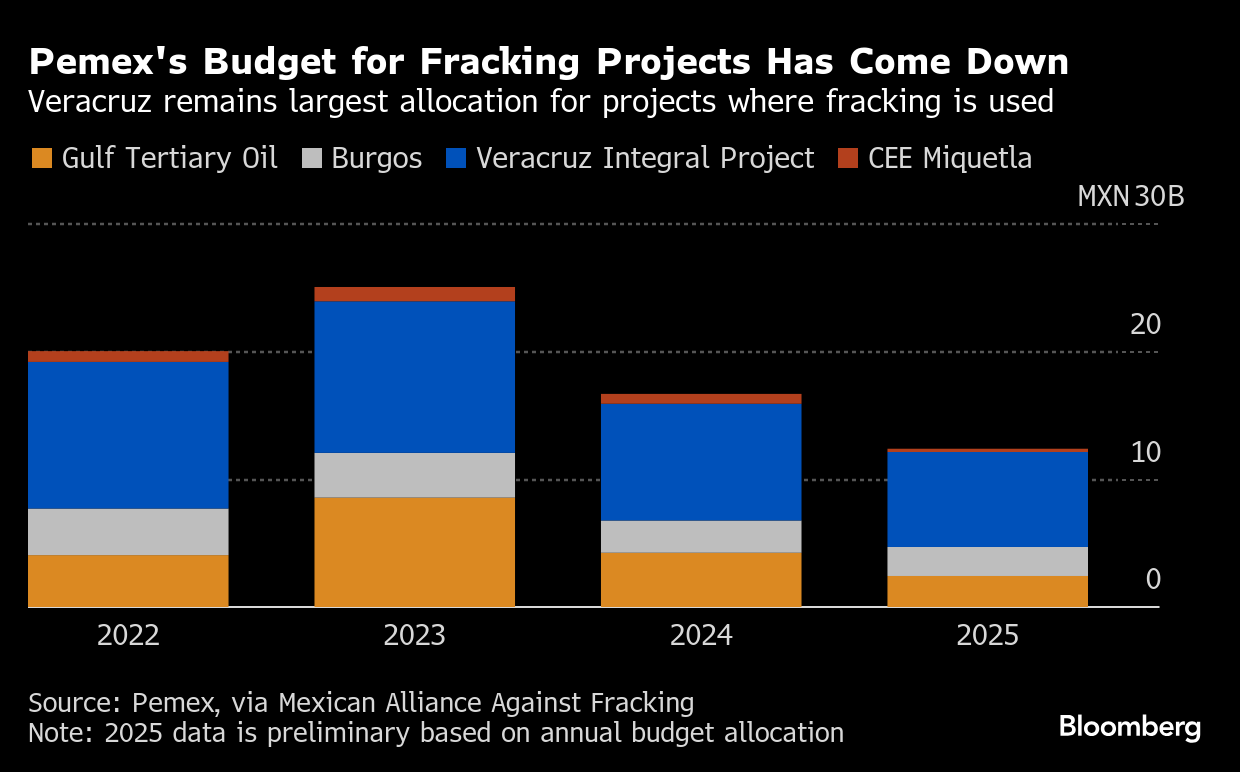

Of course, Pemex’s financial woes mean the company can’t pursue capital-intensive projects to tap shale reserves without partners. This year, the company’s allocated budget for fracking projects in four key exploration zones plunged 25% to 12.3 billion pesos ($658 million) from the year prior, or about 3% of the company’s total annual operating budget, according to Pemex data.

Sheinbaum’s challenge will be attracting investment and technology from the other side of the Rio Grande, where modern fracking techniques were invented and honed. Pemex is trying to conjure joint ventures with private-sector companies that will be limited to minority-partner status while shouldering operating costs and most of the risks.

Critics, however, say they company isn’t doing enough to lure new partners.

“The government is not really signaling a conducive environment for the private sector to come in,” said Osama Rizvi, an analyst at energy consultancy Primary Vision. “They need to do a lot more in terms of preparedness and messaging. I don’t see Mexico’s fracking industry booming anytime soon.”

Still, Rizvi sees hope for Pemex’s unconventional reserves as shale production in the US begins to plateau and Houston energy executives look for new markets. Major questions remain, including how to safely operate in territory controlled by organized crime and meager access to water and infrastructure, Rizvi said.

Sheinbaum, who was voted into office on promises to clean up Pemex, has indicated she must balance the goals of boosting Pemex’s output and protecting communities from environmental harm.

“Nothing is decided yet, and it needs to be put to the public’s consideration,” she said in one of her daily press conferences, adding that experts from Pemex and Mexico’s Petroleum Institute are studying options for exploiting unconventional deposits. “But there is an important issue: our dependence on natural gas.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.