Colombia Warms to Fossil Fuels as Climate Agenda Fizzles

(Bloomberg) -- Colombia, the world's only significant oil producer to join a bloc of nations vowing to quit fossil fuels, is poised for an about face.

As President Gustavo Petro’s term winds down, most prominent candidates running to replace him are promising to put oil and gas back at the forefront of the nation’s energy policy. Even moderate and center-left candidates are calling for Colombia to start using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which Petro has pushed to make illegal.

“If God gave us oil, coal and gas — we’ll use oil, coal and gas,” Claudia López, a former Bogotá mayor with a record of supporting progressive causes, said in an X post.

Petro, Colombia's first leftist president, made global headlines in 2023 by announcing the nation would sign the “fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty” to end oil, gas and coal production. It made the one-time Marxist guerrilla fighter a celebrity at international climate gatherings and brought heft to the non-proliferation movement, which until then was made up of mostly small island nations.

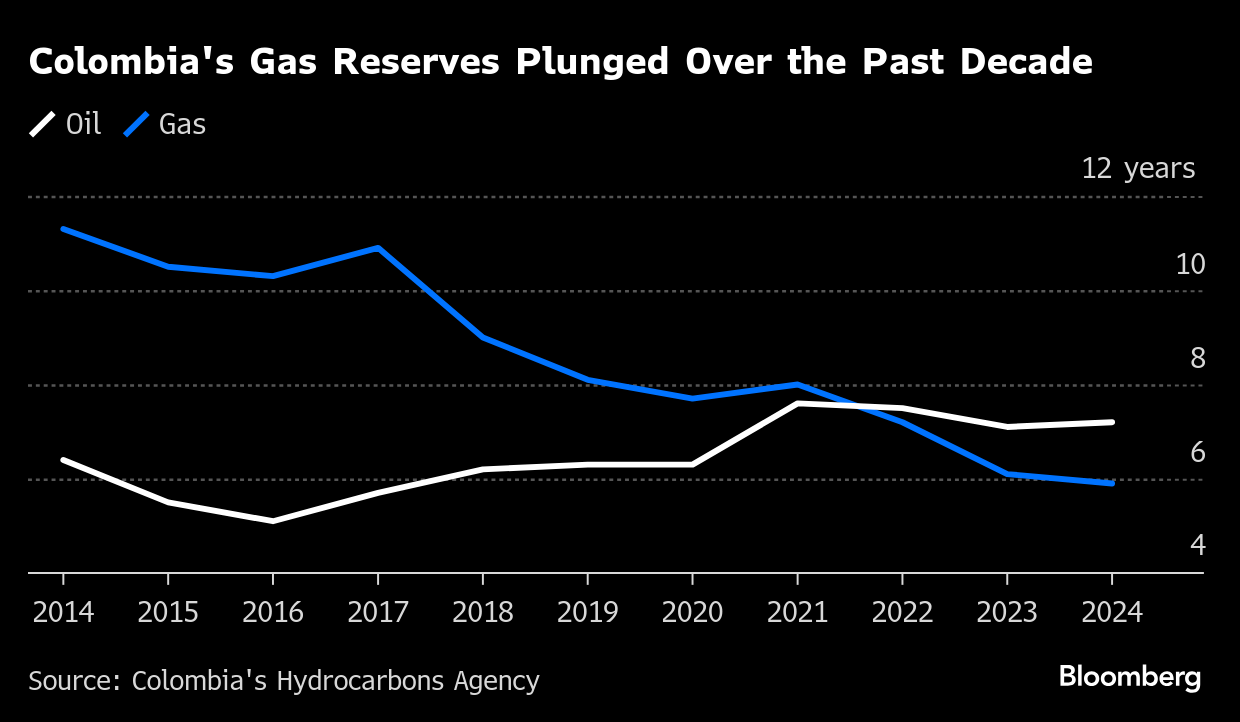

The effort, however, backfired in Colombia. Petro's refusal to allow new drilling contracts exacerbated a domestic gas shortage, forcing the nation to import fuel at higher prices. Now with Petro’s popularity waning amid rising violence and a ballooning fiscal deficit, presidential hopefuls are distancing themselves from his policies, including energy.

During a recent event in Bogotá, five candidates held up “YES” signs when asked if they would authorize fracking in Colombia. Only one, Petro’s former environment minister Susana Muhamad, said no.

The shift in Colombia reflects a broader retreat from the fight against climate change globally. In the US, President Donald Trump is gutting Joe Biden's climate policies, blocking renewable energy projects and withdrawing from the Paris climate accord. And the European Union is struggling to pass laws requiring further ambitious emissions cuts and walking back many of the business obligations designed to meet them.

It also comes as several Latin American nations, notably Guyana and Argentina, are aggressively expanding oil and gas drilling. Even Brazil, host of next month's UN climate conference and the region’s top oil producer, is pushing to significantly expand exploration, including near the mouth of the Amazon River where environmentalists have tried to block drilling for years.

Colombia, Latin America’s sixth largest oil producer, isn’t holding its election until May. The next round of polls can’t be released until next month, and the outcome remains uncertain. Yet already, investors are positioning themselves for the energy pendulum to swing back to oil and gas.

Juan Manuel Galán, who was part of a centrist coalition running against Petro in 2022, opposed fracking during the last election. Now he’s for it.

“The debate in Colombia is no longer about whether to use fracking or not,” Galán said. “Rather it’s about how to implement fracking that is environmentally responsible.”

Before Petro came to power, the nation’s energy company, Ecopetrol SA, had two pilot fracking projects in the works with ExxonMobil Corp. The technique — which uses water, chemicals and sand to crack oil and gas from shale rock — has revolutionized production in the US and, more recently, Argentina. Petro, who has called fighting climate change a matter of “life or death,” killed the effort.

Oil and coal account for about half of Colombia’s exports, meaning Colombia had a lot to potentially lose by walking away from fossil fuels. To mitigate that, Petro’s environment minister announced during New York Climate Week in 2024 that Colombia planned to invest $40 billion to replace oil and coal export revenues, raising money with help from the Inter-American Development Bank. The effort, however, hasn’t materialized, in part because of a lack of US support after Trump’s election.

While Colombia already faced potential gas shortages when Petro took office, his critics say the fracking projects he scuttled could have helped bring new sources of gas online quickly to avoid a shortfall. The Colombian Association of Geologists and Energy Geophysicists estimates fracking could boost the nation’s gas reserves by up to 50 times.

By early 2025, the nation’s gas supply had grown tight enough that it was increasing imports of liquefied shipments of the fuel, driving up prices. This month, Ecopetrol was forced to free up some of the gas it uses for its refineries and production to avoid having to ration supplies to industrial users while an import terminal was down for maintenance.

Petro, however, has held firm. In July, his environment minister re-introduced a bill to make fracking illegal — the administration’s sixth attempt. Critics say it’s time the nation moved on.

“Colombia is facing a reality check,” said former mines and energy minister Tomás González. “We now depend on gas imports, and that hurts people’s pockets.”

At an energy conference last month in Barrancabermeja, leaders of an oil labor union who once condemned fracking were calling for it to be put to use. Colombia must be ready to resume fracking pilots as soon as a new government is sworn in on Aug. 7, Cesar Loza, president of Unión Sindical Obrera, said at the event.

“We’re facing a dilemma: do we continue to import gas or do we look for it in Colombia?” he said. “We need to guarantee Colombia’s energy self-sufficiency.”

Still, resistance remains. Outside the event, Yuvelis Morales was among around 20 activists who are part of the “Colombia Free of Fracking Alliance.” Fracking, she said, threatens water for farming and fishing in her hometown of Puerto Wilches, where the pilot projects were planned.

“We’ve had oil exploitation in this region for over a century,” she said. “You go to the communities and what do you see? You see poverty, you see people displaced by violence — and you see pollution.”

A poll by the consultancy Arteaga Latam found support remains low for fracking in Colombia’s oil-producing areas — but it’s growing. About 20% of those polled say they support the technique — double the percentage of 2019. If fracking is tied to finding more gas, its approval rating rises to 42%.

The mayor of Puerto Wilches, however, says fracking would boost tax revenue and jobs in town. “We’re all going to benefit,” Mayor José Elías Muñoz said.

The evolving debate in Colombia is a reminder of the formidable challenges nations face when trying to overhaul century-old energy systems, said Luisa Palacios of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

“The swing back to fossil fuels is a moving factor that is related to politics but also to fundamentals,” she said in an interview. “In developing economies that have so many needs -- fiscal needs, export needs and foreign currency needs -- you cannot afford not to be pragmatic.”

(Updates with detail about public support in Colombia for fracking. A previous version was corrected to remove inaccurate reference to UK clean-energy targets.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.