Climate Talks Enter Crunch Time at COP30 Summit in Brazil

(Bloomberg) -- Negotiators leading United Nations climate talks in Brazil laid out options for addressing the world’s disappointing progress in curbing greenhouse gas emissions, though countries remain far apart on finance and trade policy.

The nine-page draft agreement unveiled Tuesday at the COP30 summit leaves unresolved several contentious topics, reflecting deep divisions over how to help developing countries adapt to global warming and how nations should live up to their 2023 commitment to transition away from fossil fuels.

The draft text comes one day before Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is slated to return to the talks in Belém to try to boost ambition in the negotiating rooms. Lula led calls at the start of the conference for road maps to address deforestation and the transition away from fossil fuels, though the proposal Tuesday falls short of that approach. The Brazilian COP30 presidency is aiming to conclude a first “package” of decisions Wednesday.

Lula’s presence “could be something that has an influence on the pace of the negotiations,” said David Waskow, an international climate director with the World Resources Institute.

The text follows more than a week of talks in the rainforest city of Belém, as COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago urges countries to come together and unite behind what he’s calling the “ decision,” invoking a Brazilian term for collective effort.

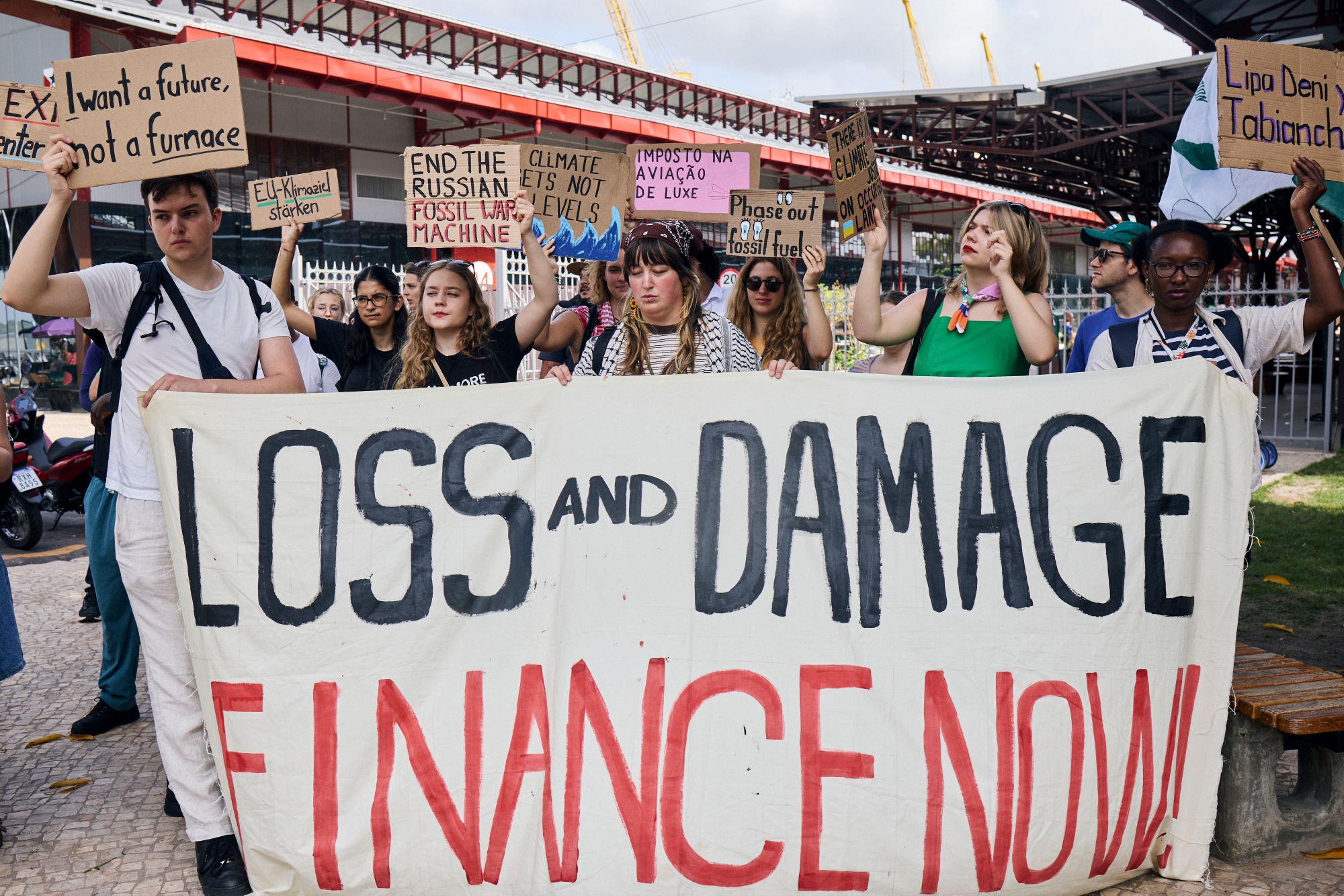

Activists complained that much of the proposal isn’t sufficient to address the use of fossil fuels driving climate change — or to support poor nations working to develop their economies without them.

The proposals “largely miss the mark for the level of ambition that this COP requires,” said Rachel Cleetus, senior policy director for climate and energy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Cleetus called the plan “far too weak” on phasing out fossil fuels and “woefully lacking” on finance.

Here’s how the so-called options text would address key issues:

Closing the emissions gap

The proposal recommends three approaches for responding to a shortfall between the emissions reductions that countries are making or have committed to and what’s actually needed to fulfill a Paris Agreement goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C from pre-industrial levels.

A first option would set up an annual “consideration” of the issue, to address the shortfall, enable knowledge sharing and strengthen country commitments. A second would see the launch of a new, voluntary “Global Implementation Accelerator” that would seek to support countries in implementing their carbon-cutting pledges and expedite action, culminating in a later report on the work.

A third proposal would create a new “Belem Roadmap to 1.5,” identifying ways to accelerate work and addressing international cooperation and investments in countries’ carbon-cutting commitments, with a report due at next year’s climate summit.

Transitioning away from fossil fuels

Two years after nearly 200 countries agreed to transition away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly and equitable manner, they are now debating proposals to further define what that looks like in practice.

It’s not clear that the COP30 meeting will address the issue squarely in any final agreement. The draft document released Tuesday outlines two concrete options — plus a third, which is no text at all.

Under one of the proposals, seen as the strongest option, countries would be encouraged “to cooperate for and contribute to” global efforts to shift away from fossil fuels, with a high-level ministerial roundtable meant to help nations create transition road maps and “progressively overcome their dependency on fossil fuels,” as well as to aid them in “halting and reversing deforestation.”

A second proposal would set up a workshop for countries to share “domestic opportunities and success stories” on the shift toward “low-carbon solutions.”

“We must build on the presidency’s ideas for a pathway on the transition away from fossil fuels because there is no answer to the climate crisis without action on this issue,” Ed Miliband, UK secretary of state for energy security and net zero, said at COP30 Tuesday.

Finance for developing nations

The draft also reflects a longstanding tension over how to provide climate finance to developing countries. Many poor countries are burdened by trying to build their economies without fossil fuels and must adapt to climate impacts they had little hand in creating.

Richer, developed nations have long been put under pressure to meet finance obligations under the Paris Agreement.

One of the proposed solutions would set up a “legally-binding” plan to do so — something the likes of the EU will be loathe to accept. Under that approach, the binding plan could include development of a common system to track and report on climate finance as well as the creation of “fair burden-sharing arrangements” among developed nations.

Another option would create a new work program, with separate tracks meant to mobilize additional finance and make more of it concessional.

A third proposal would result in a two-year work program to address barriers to boosting finance, including the reform of international financial institutions.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.