Regulators Probe Why Williams Took More Than an Hour to Halt a Methane Leak

(Bloomberg) -- When a farmer accidentally ruptured a pipe while using an excavator last October, it took its operator — Williams Cos. — 65 minutes to isolate the leak. By the time it did, the line had emitted methane with a short-term climate impact roughly equal to the annual emissions from 17,000 US cars.

Both Williams and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) said the accident could have been prevented if the farmer had called a program that marks the location of underground pipes with paint or flags for homeowners prior to any excavation or digging work. But PHMSA is also examining “the time it took the operator to respond to and isolate the release” as part of an investigation into the incident.

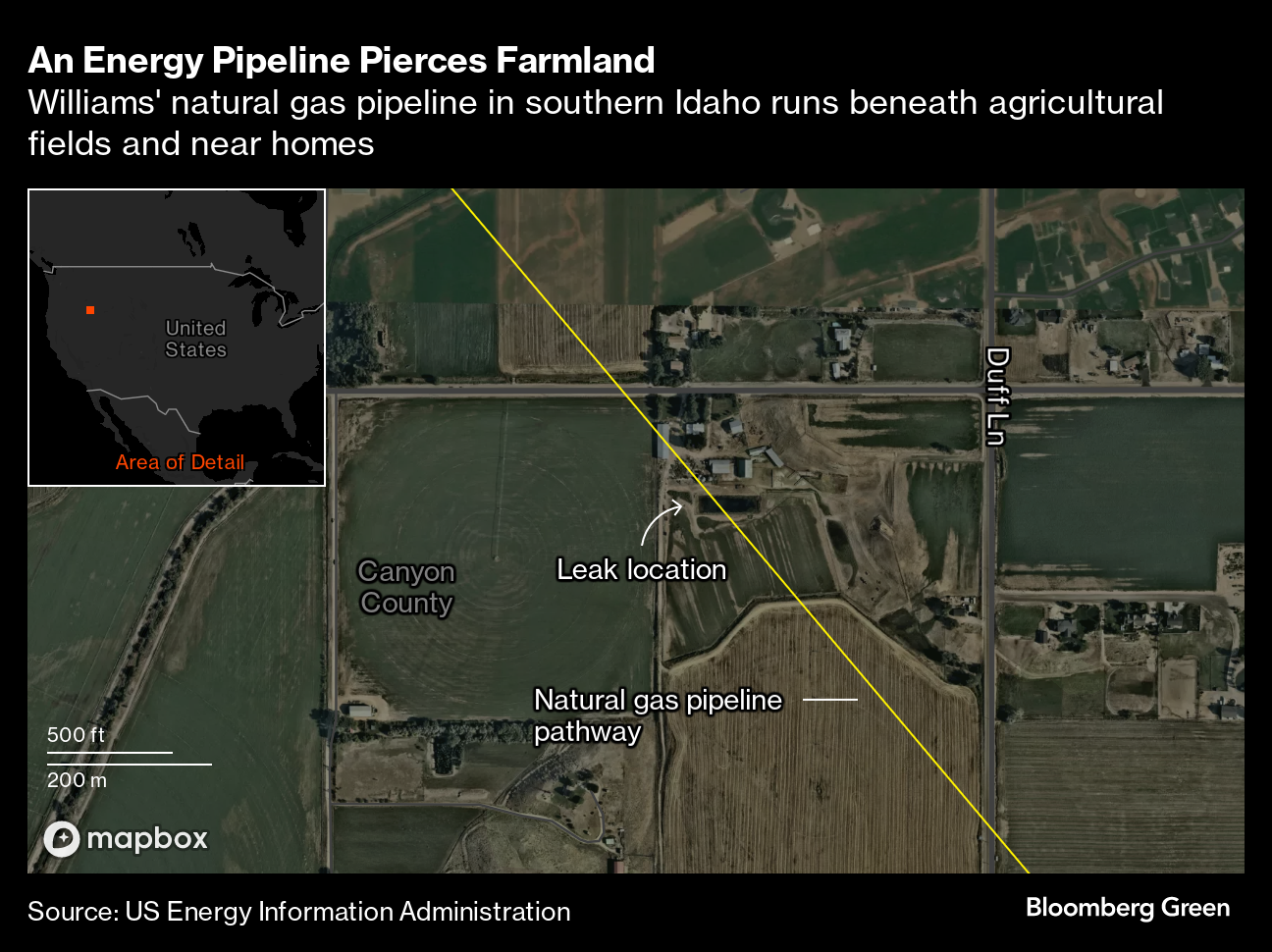

US pipeline operators are required to respond to and isolate leaks at the earliest practical moment possible, but because each network is unique, response times can depend on many factors. Those include the use of manual or remote valves, the distance between valves and location of the release. The line involved in the October rupture runs under agricultural fields where the accident occurred in Canyon County, Idaho.

The accident shows why PHMSA recently passed a rule that applies to large, new pipelines and replacements that requires operators to use valves that can automatically shut so leaks do not exceed 30 minutes. An incident report for the Idaho leak shows even though Williams “immediately dispatched” workers to two valves about 10 miles (16 kilometers) apart to isolate the ruptured segment, the upstream valve — which was remotely controlled — shut 29 minutes before the manual downstream one.

“Over an hour is a long time to shut in a pipeline after a failure,” said Bill Caram, executive director of the Bellingham, Washington-based non-profit Pipeline Safety Trust. “Rupture mitigation valves such as automatic or remote-controlled valves theoretically could have reacted much quicker.”

In addition to spewing a gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide, the accident also had a significant impact on the nearby community. Authorities evacuated residents within a four-mile radius of the accident. A local emergency management report from the Middleton Star Fire District said that responders approaching the site heard “a loud roar that sounded like a jet engine and the ground could be felt shaking from 1/4 mile away.”

In its report to PHMSA, Williams said that it didn’t plan to investigate controller or control room issues related to the incident, although in an email to , it emphasized it was “conducting a full review of the event.” The company initially said it isolated the damaged section of pipeline “within an hour” but didn’t answer to follow up questions about how it determined that timeline. The PHMSA report showed the procedure took 65 minutes and an official with the agency confirmed that duration.

The farmer, who was using the excavator to clean out a pond, was taken to the hospital by his family and discharged later in the day with no significant injuries, according to a PHMSA official and the incident report.

The massive leak was observed and quantified by scientists using a breakthrough technique to analyze satellite observations that enables near continuous and real-time observations of the potent greenhouse gas.

The approach uses observations from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration geostationary weather satellite that orbits the planet at an altitude of 22,236 miles and moves at the same rate and direction that the Earth spins, enabling nearly continuous coverage. Other satellites used to detect methane are in lower orbits and snap images as they circumnavigate the globe at speeds of around 17,000 miles per hour.

Geoanalytics firm Kayrros SAS estimated the event spewed about 840 metric tons of methane and said the massive plume was visible in satellite data for five hours and drifted 75 miles before dispersing. Williams said the incident released 50.9 million cubic feet of gas. Assuming it was composed of 95% methane — the standard for processed gas — that works out to about 900 metric tons of methane.

Excavator damage is one of the leading causes of pipeline incidents in the US, according to PHMSA, which is a division of the Department of Transportation. In Idaho, the state’s call-before-you-dig service available for home owners and contractors requires two days notice before intent to dig.

The 22-inch (56-centimeter) diameter Williams pipeline was installed in 1956 and buried at a depth of 36-inches below the surface, according to the PHMSA report. There were four sets of pipeline markers approximately 225, 600, 700 and 1,600 feet away from the incident site and “additional line markers that had been removed were also discovered within the vicinity,” according to an official with the agency.

The release was also tracked by scientists at the United Nations’ International Methane Emissions Observatory.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.