Brazil Tries to Sell Skeptics on ‘Low-Carbon Beef’ at COP30

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s meat industry is mounting a campaign to convince the world it can produce beef with low carbon emissions — a claim that some experts say obscures beef’s heavy toll on the climate.

Leia em português

At the COP30 climate summit in the Amazonian region, ranchers, government-backed scientists, and major meatpackers are offering a new storyline for an old staple. They argue that with careful management, the same fields where cattle graze can pull carbon from the air, countering the environmental damage from the methane those animals release.

The sector is planning a series of events in Belém to make its case. On Wednesday, lobby group Abiec released a study on reducing emissions from cattle farming inside the summit’s Agrizone Pavilion, a specially dedicated area at COP30.

Meanwhile, pasture carbon-capture trials of farming group Roncador are being showcased in a prominent booth. Later in the week, the state-owned agricultural research company Embrapa will unveil a manual outlining the steps producers must take to qualify for a “low-carbon” label.

“What we have in our hands is a plan for how Brazil can make its beef sector reach its full potential to contribute to the climate agenda,” said Fernando Sampaio, sustainability director at Abiec.

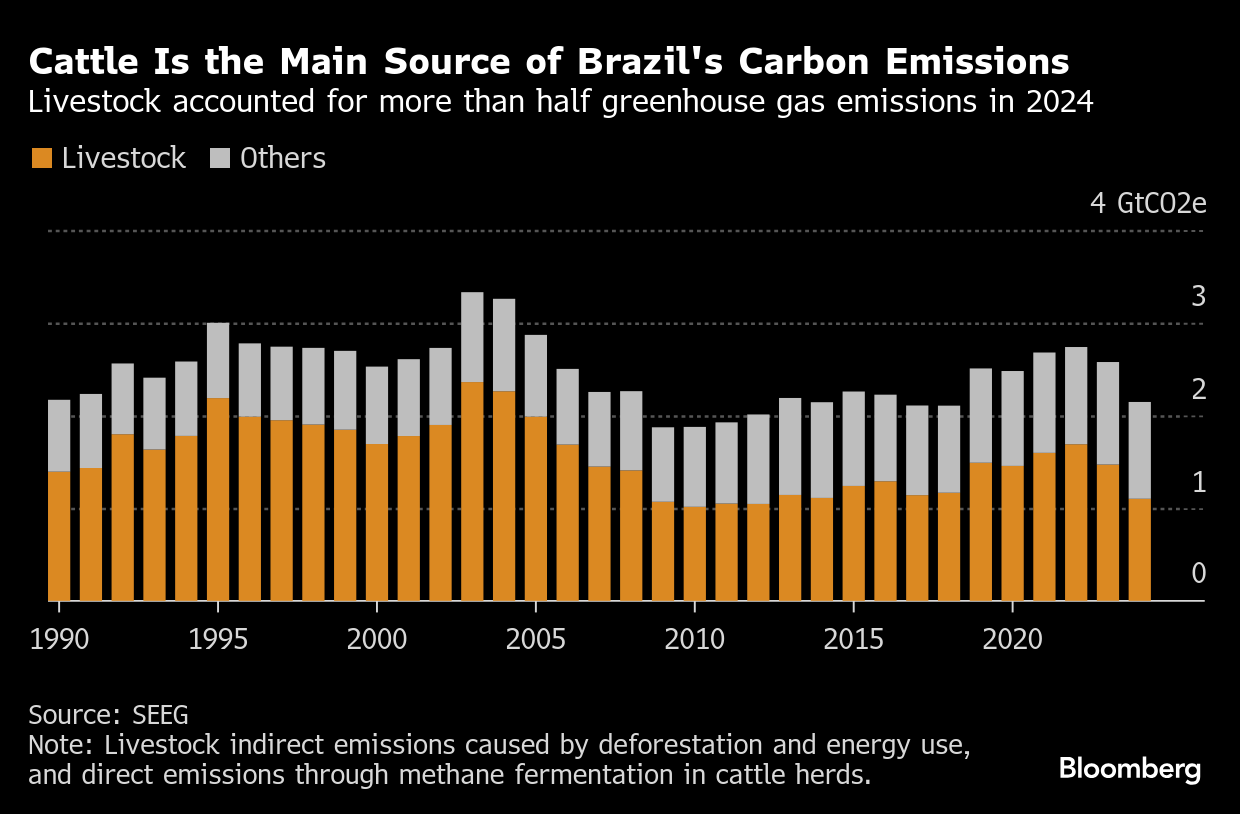

Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of beef, and agriculture is a pillar of the economy. But the industry faces intense international scrutiny for its hefty carbon footprint and role in deforestation.

Cows burp out large amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas that’s far more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term. That makes beef far more polluting than other sources of protein. A 2018 Science study found that producing one kilogram of beef generates roughly 100 kilograms of greenhouse gases — about eight times more than pork and 20 times more than eggs.

“Cattle’s methane emissions is a still really significant part of the climate change problem,” said Pete Smith, a professor of soils and global change at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland.

In Brazil, where cattle are mostly grass-fed, that impact is magnified by the cutting down of forests for new pasture, which releases the forests’ carbon. Since 1985, about 13% of the rainforest has been turned into pasture or cropland, according to Climate Observatory’s MapBiomas.

Embrapa argues that Brazil’s vast grasslands can also be part of the solution — they are capable of capturing carbon if managed properly, through techniques such as nutrient enrichment and erosion control, and if the land hasn’t been cleared since 2008.

A study by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, in partnership with Abiec, released on Wednesday, found that the sector could cut emissions on a large scale by 2050 if it continues adopting more efficient production practices and curbing the conversion of new land into pasture.

To certify farmers who have good practices and are able to produce “low-carbon beef,” Embrapa has developed a protocol with a list of requirements to be met. The project is backed by meatpacking giant MBRF Global Foods Company SA, and about 10 of the company’s suppliers are set to be certified soon, said Embrapa’s researcher Roberto Giolo.

Improving carbon stocks in grasslands is technically possible but nowhere near enough to offset the methane cattle produce, said Smith. He noted that soil carbon sequestration only lasts for a limited time — until the soil reaches equilibrium with the ecosystem and stops absorbing carbon — while cows grazing on that land will keep emitting methane.

“Soil management should be improved. But it won’t offset the methane emissions,” said Smith. “This is a disingenuous claim that it is contributing to the climate change solution.”

Brazil’s case for cutting emissions from beef rests on the fact that many ranchers still fall short of the country’s own standards for soil management — meaning even modest improvements could yield significant climate gains.

Roughly half of Brazil’s grasslands show some degree of degradation, according to University of São Paulo researcher Carlos Eduardo Cerri, who studies carbon emissions in agriculture. Degradation occurs when cattle overgraze, stripping away vegetation that protects the soil and allows it to store carbon.

That’s where farming group Roncador comes in as a showcase for the sector’s efforts to better manage the soil.

Roncador combines crop production and cattle ranching to speed up soil recovery. The model was originally designed to boost productivity, said Roncador’s owner, Pelerson Penido Dalla Vecchia. But he later noticed environmental benefits as well.

The group has long opened its fields to researchers studying soil carbon. The latest effort comes from a team at Kansas State University, which began soil sampling on one of the group’s farms. The research is ongoing and results are still unknown.

Efforts to improve efficiency in grazing make sense, but are not a “get out of jail free card” for big beef, said Jonathan Foley, executive director of Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization that focuses on climate solutions.

“It’s like taking a very dirty old car and replacing it with a new car,” said Foley. “In terms of everyday things we use in our homes, beef is by far the biggest polluter, and no amount of soil carbon is going to offset that.”

Industry representatives pushed back against the criticism, pointing to how degraded land can be replanted with grass, then with crops and other vegetation for what Brazilian agribusiness calls a “crop-livestock-forestry integration.”

“You combine carbon capture with productivity — and you should never look at one without the other,” said Minerva SA’s sustainability director, Marta Giannichi.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.