Energy Guru Is ‘Beyond’ Disappointed With Dwindling U.S. Infrastructure Plan

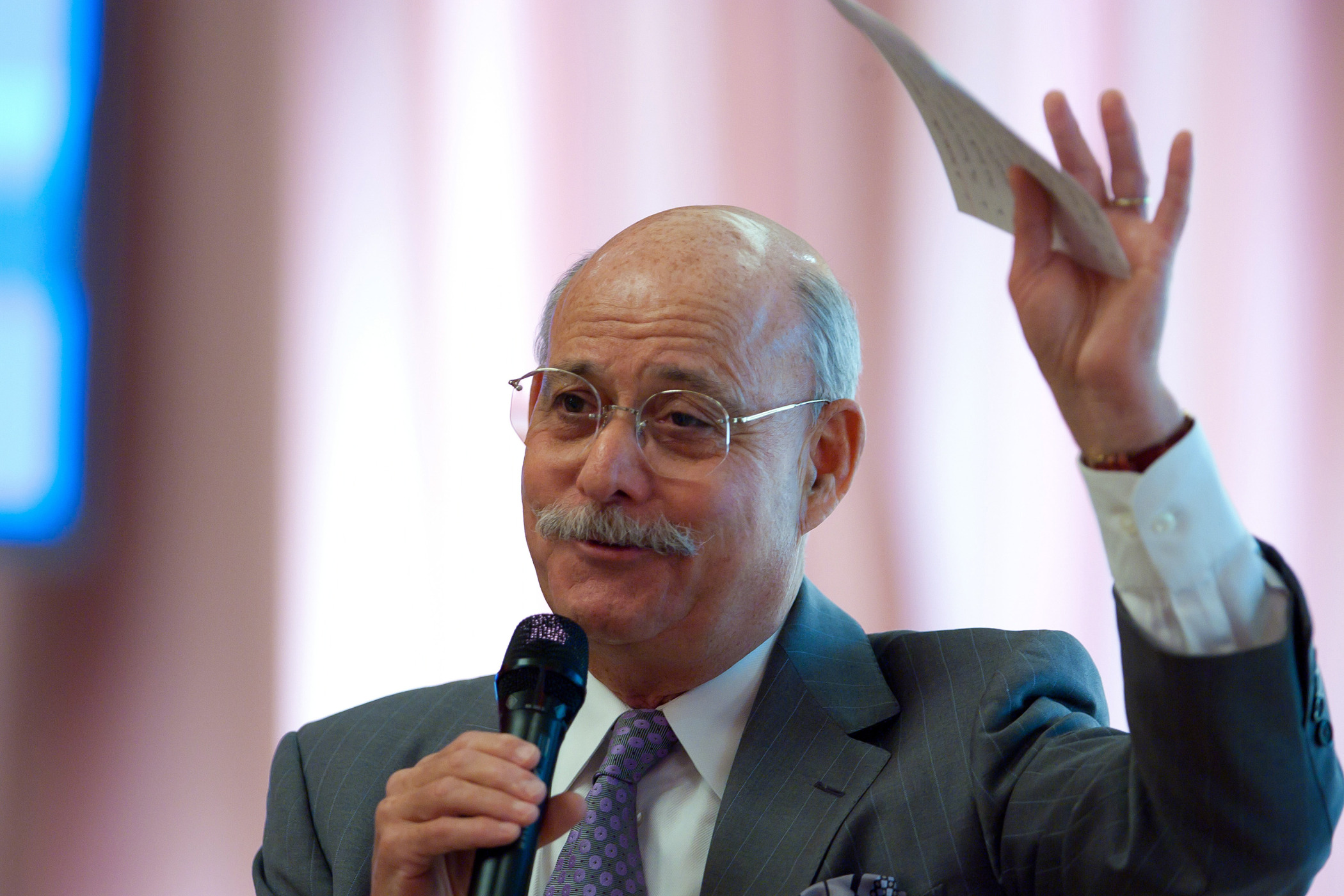

(Bloomberg) -- For almost two decades the U.S. author and climate activist Jeremy Rifkin has advised governments in Europe and China on how to retool their economies for what he calls a third industrial revolution. But never his own.

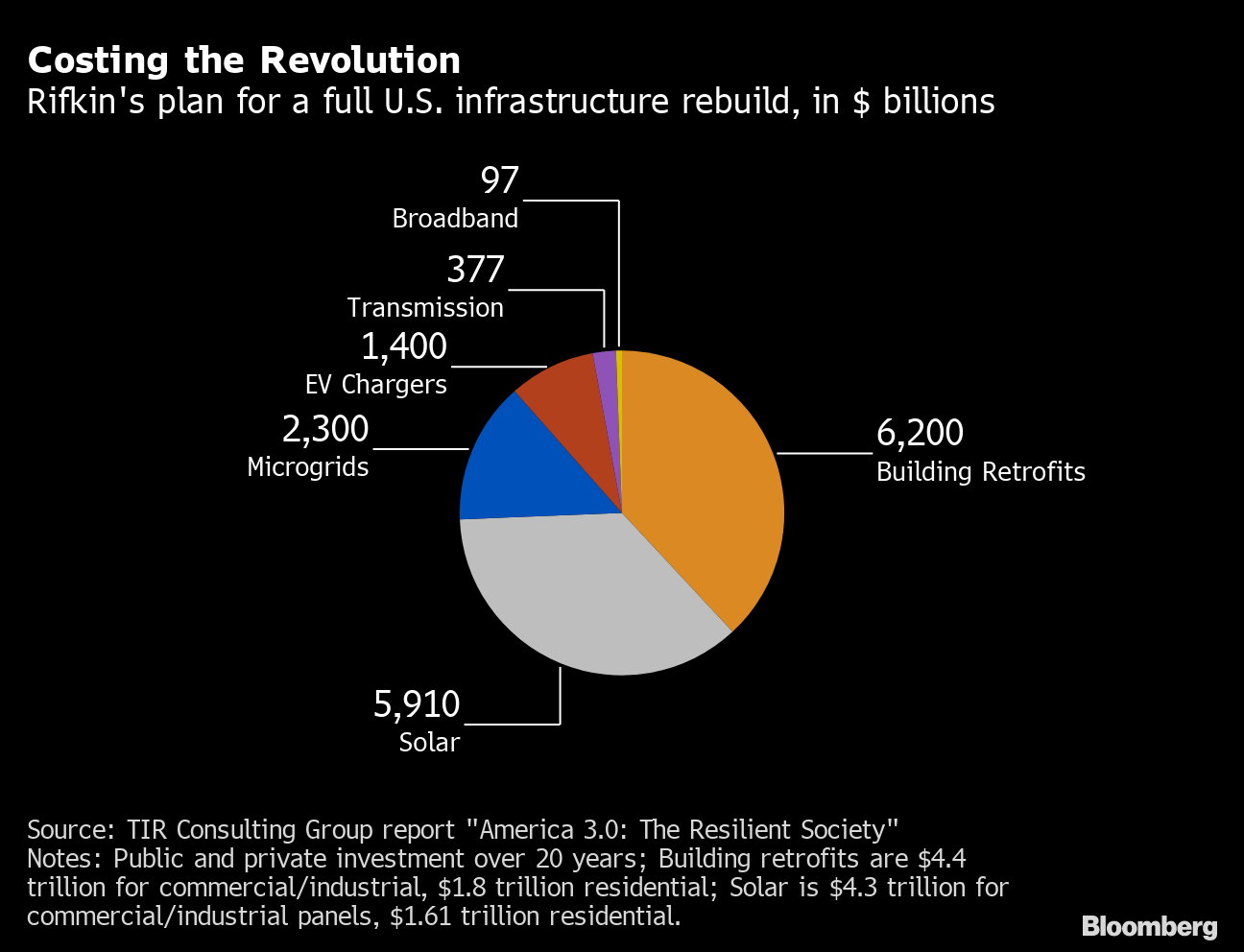

That seemed to change lately, allowing Rifkin to dream of aligning the digital policies and energy infrastructure of the world’s economic superpowers, a goal he says could one day see electricity traded across continents and help reduce geopolitical tensions.Rifkin met seven times in recent years with now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer to discuss his ideas. That included a dinner Schumer hosted at a Capitol Hill restaurant in July 2019 to persuade seven other Democratic Party senators to support a big ticket reinvention of American infrastructure.Alongside a team that included construction multinational Black & Veatch and Chicago’s Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, Rifkin also wrote a 242-page, 20-year, $16 trillion strategy for Schumer on how the U.S. could reboot productivity growth while meeting climate targets.

At least one proposal that the report’s authors claim as original — to bury a new high voltage direct current grid under federal highways and railways — also appeared in the American Jobs Plan that President Joe Biden unveiled in March, though it's hard to identify the source of any one idea in the sausage-making of legislation.

Rifkin’s blueprint “underscores the need to pass big, bold solutions to address climate change through investments in our infrastructure,” Schumer said in a written response to questions. The report, accessible here, was held private until now.

Yet as the administration’s infrastructure proposals enter the shredder of a polarized Congress, Rifkin’s losing hope.

A deal negotiated by a group of Republican and Democratic legislators cuts Biden’s $2.25 trillion plan to about half a trillion, of which Rifkin says roughly $150 billion would be spent — over eight years — on what he considers the renewable and digital infrastructure essential to the U.S.’s ability to compete. The rest is mainly to update “old” technologies, such as roads and bridges.

“It’s beyond disappointing,” Rifkin says. “If it holds it will likely put the United States out of the game vis-a-vis the EU and People’s Republic of China” with their trillion-dollar-plus digital and energy investment programs.

Rifkin is given to sweeping statements and acknowledges that most investment for any U.S. infrastructure revolution would come from states and the private sector. Schumer, meanwhile, is pushing a parallel $3.5 trillion bill that would resurrect some of the lost provisions.

But to meet climate targets and reboot the economy the government needs a more comprehensive strategy even if there is less money in the pot and, on that front, the latest Biden plan also falls short, according to Rifkin and his team.

Biden’s original package had already drawn criticism from environmental groups as inadequate.

It offered $100 billion for a transmission system including the underground grid. It said nothing about integrating that supersized network with the microgrids that in future are likely to account for about 50% of U.S. power capacity additions, according to Rob Wilhite, senior vice president and managing director for global distributed energy at Black & Veatch, which installs electricity grids.In the team’s blueprint, the sub-highway grid would consist of 22,000 miles of cable, costing $377 billion in public and private investment. It would hook up to a network of more than 74 million microgrids, costing $2.3 trillion. Overall, their report claims it would add 15 million to 22 million net jobs to the U.S. payroll, and 0.4 percentage points to annual economic growth.

To Rifkin’s critics, the puzzle isn’t that he’s ignored in Washington, but that he gets so much attention elsewhere.A life-long activist of protest causes from the Vietnam War, to biotech to eating beef, Rifkin drew a 1989 Time magazine headline “The Most Hated Man in Science” for his attacks on bioengineering experiments that later proved safe.His current expectation that renewable energy and the internet will help create a so-called sharing economy, less dominated by massive corporations and inter-state conflict, looks at best premature. Tensions between the U.S. and China are rising while the tech space is dominated by giants such as Amazon.com Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google.

Biden Faces Hard Sell in Asia for Anti-China Digital Trade Pact

Still, there's no doubting Rifkin’s influence outside the U.S. When he sent his American blueprint to Maros Sefcovic, the European Commission vice president in charge of “Future of Europe” plans, the response was an excited “let’s talk.”“Mr. Rifkin’s ideas certainly inform our thinking in the European Union on energy – perhaps not surprising given that he is an advisor to us,” Sefcovic said in an emailed response to questions. “The opportunities offered up by the green and digital transitions, as he identifies, are huge.”

Former German Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel says he first invited Rifkin to address a 2007 meeting of environment ministers, where the American helped break a deadlock over Europe’s first climate target. It wasn’t what Rifkin had to say on climate that was compelling, according to Gabriel. It was his argument — then controversial, but by now conventional wisdom — that the shift to renewable energy was an opportunity for wealth and job creation.

“We were having all these interesting climate conferences where officially we negotiated climate targets, fine, but unofficially it was all about economic success,” Gabriel said, adding that countries like China, India and Brazil were convinced the whole climate debate was a ruse to burden them economically.

Chinese leaders have come around since. Rifkin’s 2011 book “The Third Industrial Revolution” sold more than half million copies in China, according to a 2021 royalties statement, not least because Premier Li Keqiang wrote about it in his biography and told officials to read it. The government also invited Rifkin to Beijing.At a 2015 United Nations conference, President Xi Jinping proposed Rifkin’s vision of a global, integrated “energy internet.” Language and ideas from Rifkin’s books marked the government’s two five-year economic plans since. When the industry ministry launched a Digital Silk Road to accompany China’s Belt and Road Initiative, he was drafted to write the foreword.

The Future of Power Is Transcontinental, Submarine Supergrids

That high-level interest was down to timing, says Changhua Wu, a Beijing-based academic who runs Rifkin’s office in Beijing. “The Third Industrial Revolution” emerged as a new team took power in Beijing, and as the global financial crisis left the Western model of economic development tarnished.Rifkin “offered just the kind of narrative the Chinese leadership were desperately looking for, one that said: This is the future,” says Wu.Why his ideas have found less traction in Washington is a question Rifkin struggles to answer, though he says the U.S. could turn things around quickly if it chooses.But if there is a reason for the reluctance, he thinks it’s that the U.S. gained most from the second industrial revolution — the late 19th and early 20th century one founded on the telephone, electrification, the combustion engine and oil — and as a result finds it hardest to let go.“If you are living off past successes,” he says, “you want to keep repeating them.”

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More renewables news

GE Vernova Expects More Trouble for Struggling Offshore Wind Industry

GE Vernova to Power City-Sized Data Centers With Gas as AI Demand Soars

Longi Delays Solar Module Plant in China as Sector Struggles

Australia Picks BP, Neoen Projects in Biggest Renewables Tender

SSE Plans £22 Billion Investment to Bolster Scotland’s Grid

A Booming and Coal-Heavy Steel Sector Risks India’s Green Goals

bp and JERA join forces to create global offshore wind joint venture

Blackstone’s Data-Center Ambitions School a City on AI Power Strains

Chevron Is Cutting Low-Carbon Spending by 25% Amid Belt Tightening