Putin’s War in Ukraine Pushes Ex-Soviet States Toward New Allies

(Bloomberg) -- Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine partly to assert Russia’s regional dominance once and for all. Nearly a year on, the Russian president has achieved the opposite — and not just in Kyiv.

Officials from ex-Soviet states in central Asia and the Caucasus say the war has prompted their governments to look for ways to reduce dependence on Moscow by turning to rival powers including Turkey, the European Union and Middle East countries. All spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid antagonizing the Kremlin.

Current and former Russian officials, also speaking on condition they not be identified, said Moscow is reacting nervously, even harshly, as the Kremlin becomes less certain of its ability to assert influence in its own backyard.

Russia has been for decades “a veto player, a gatekeeper in northern Eurasia where nothing much could happen if the Kremlin didn’t like it,” said Ekaterina Schulmann, a Russian political scientist now based in Berlin. “Now that seems to be changing” with Russia unlikely to emerge stronger from the war in Ukraine, and “this makes dictating one’s will to neighbors problematic, to say the least.”

While the failure of a key Kremlin war aim is clearest in Ukraine and Moldova, which applied for EU membership and gained candidate status after the conflict erupted, the invasion has forced even traditional friends such as Kazakhstan and Armenia to actively build ties with powers that Moscow long sought to keep at bay in the region. That has allowed Turkey in particular to step in to the void.

Announcing his Feb. 24 invasion, Putin at the time cited Kazakhstan as a model for the kind of relationship he wanted Russia to have with ex-Soviet states. He’d sent troops to help President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev crush deadly riots only the previous month.

Yet Tokayev has since disagreed openly with Putin’s justification for the war, while allowing hundreds of thousands of Russians to flee to central Asia’s largest oil exporter after Russia announced mobilization in September. Schulmann, who was designated a “foreign agent” by the Kremlin days after she left Russia in April, was welcomed in Kazakhstan this month by the head of its Senate, the country’s second-highest official, and offered a professorship at one of its universities.

“Russia is becoming more and more toxic,” said Beibit Apsenbetov, a former board member of Kazakhstan’s largest bank, Kazkommertsbank JSC. “What to do when your neighbor is a drunkard and rowdy, and you can’t move out?”

Russia has appeared to show its displeasure with Kazakhstan by repeatedly interrupting flows through the 1,500 km (932 miles) Caspian Consortium Pipeline (CPC), citing technical or regulatory issues. The pipeline through which Kazakhstan sends about 80% of its oil exports crosses Russia to the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, less than 100 miles from occupied Crimea.

In November, Kazakhstan said it would increase oil exports across the Caspian Sea by 1.5 million tons by feeding oil into the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, which runs from Azerbaijan to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. Tokayev said flows along the route, which bypasses Russia, could eventually rise to 20 million tons. Kazakhstan sent more than 50 million tons through the CPC in 2021.

The route adds to the so-called Middle Corridor for China-Europe rail cargo, which runs via Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey, and has seen a sharp increase in demand; the war has reduced traffic on the less complicated Chinese rail link to Europe, via Russia and Belarus.

In the past year, Tokayev also encouraged defense ties with Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and traveled to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates to boost trade and investment cooperation.

Neighboring Uzbekistan, heavily dependent on trade with Russia, was looking to open up even before the war. It signed an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement in July with the EU. In December, after the second meeting of a new Strategic Partnership Dialogue with the US, a joint statement welcomed the nation’s “willingness to establish new trade routes and diversify import and export markets.”

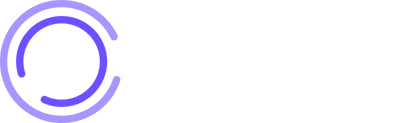

To be sure, Russia remains a powerful force in the region. With international sanctions in response to the war blocking Russia’s westward trade routes, Moscow’s ex-Soviet neighbors have become even more important to it as conduits for trade. Exports to Russia from other members of the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union -- Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan -- have soared, as goods are rerouted from Europe. Turkish exports to Russia have also increased.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are doing their best to diversify their relations so long as Moscow is preoccupied in Ukraine, but “you can’t change geography, there are deep ties and long borders.” said Annette Bohr, an associate fellow in the Russia and Eurasia Program at Chatham House, a UK think tank. “There is no decoupling from Russia for central Asia, at least for many years.”

Still, the war and the sanctions that followed have highlighted the risks of over-dependence on Moscow, and nowhere has that become more clear than in Armenia, the Kremlin’s close ally in the Caucasus and home to its only military base there.

Disappointment is running high in Armenia at Russia’s unwillingness or inability to intervene in a long-running territorial conflict with neighboring Azerbaijan, which enjoys strong defense backing from Turkey. Officials fume over a seven-week-long de facto Azerbaijani blockade of the Lachin corridor, a vital road link to Armenians living in the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, while Russian peacekeeping troops in the area watch on.

Why Azerbaijan-Armenia Dispute Draws Big Powers In: QuickTake

“Azerbaijan is taking advantage of the situation in Ukraine,” said Sergey Ghazaryan, foreign minister of the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh government, who’s been unable to travel there from Armenia since his appointment earlier in January.

Three times this month, nationalists have staged protests outside the Russian military base at Gyumri, holding up slogans such as “Russian Occupying Forces Out of Armenia.” The demonstrations against the country’s traditional ally and protector were small, but unprecedented.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan this month announced Armenia won’t host planned military exercises of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a Russia-led alternative to NATO, after the alliance failed to respond to Armenian pleas for help following border clashes with Azerbaijan last year.

The EU announced Jan. 23 it’s sending a two-year civilian monitoring mission to patrol the border in response to Armenia’s request, in what the bloc’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell called “a new phase” of its engagement in the Caucasus.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry condemned the mission on Thursday in a statement that called the EU “an appendage of the US and NATO” and warned its involvement in the region “can only bring geopolitical confrontation.”

Azerbaijan, too, has drawn closer to the EU, signing a deal in July to double gas exports to the bloc by 2027, as Brussels seeks to replace Russian fossil fuels in response to the war in Ukraine. Last month, the EU said it would also help fund a direct power cable from Azerbaijan and neighboring Georgia to EU member states, across the Black Sea, with the potential to later connect Ukraine and Moldova.

But so far Turkey has benefitted most from Russian hesitation. With Armenia no longer assured of Russian protection, Pashinyan and Turkey’s Erdogan in October also held the first talks between the leaders of their two countries in 13 years, amid a push to establish diplomatic ties and open their border.

How Turkey Tries Balancing East and West as War Rages: QuickTake

“Putin has lost his monopoly in the Caucasus region,” said Grigory Shvedov, who heads the Moscow-based Caucasian Knot research service. “Now Erdogan is the main actor in the game.”

--With assistance from , and .

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

KEEPING THE ENERGY INDUSTRY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletter and get the best of Energy Connects directly to your inbox each week.

By subscribing, you agree to the processing of your personal data by dmg events as described in the Privacy Policy.

More oil news

US Regional Banks Dramatically Step Up Loans to Oil and Gas

Apr 14, 2024

Oil Rises to October High as Israel Prepares for Iranian Attack

Apr 12, 2024

Gold Hits New Record, Oil Rises on Mideast Tension: Markets Wrap

Apr 12, 2024

Oil Swings Near $90 With Risk of Iran Strike on Israel in Focus

Apr 11, 2024

Oil Holds Two-Day Loss as Report Points to Rising US Inventories

Apr 10, 2024

Commodity Traders Rake in Billions in Second Blockbuster Year

Apr 08, 2024

Oil Rally Takes Breather With Israel to Pull Some Gaza Troops

Apr 08, 2024

Egypt’s Gas Shortage Brings New Risks After Massive Bailout

Apr 08, 2024

Mexico’s Pemex Says Nine Injured, One Dead in Platform Fire

Apr 08, 2024

Trafigura Power Broker Who Showjumped in Olympics Is Leaving

Apr 05, 2024

Energy Workforce helps bridge the gender gap in the industry

Mar 08, 2024

EGYPES Climatech champion on a mission to combat climate change

Mar 04, 2024

Fertiglobe’s sustainability journey

Feb 29, 2024

Neway sees strong growth in Africa

Feb 27, 2024

P&O Maritime Logistics pushing for greater decarbonisation

Feb 27, 2024

Oil India charts the course to ambitious energy growth

Jan 25, 2024

Maritime sector is stepping up to the challenges of decarbonisation

Jan 08, 2024

COP28: turning transition challenges into clean energy opportunities

Dec 08, 2023

Why 2030 is a pivotal year in the race to net zero

Oct 26, 2023

Low carbon hydrogen holds the key to achieving net zero

Sep 29, 2023Partner content

Ebara Elliott Energy offers a range of products for a sustainable energy economy

Essar outlines how its CBM contribution is bolstering for India’s energy landscape

Positioning petrochemicals market in the emerging circular economy

Navigating markets and creating significant regional opportunities with Spectrum