UK’s Energy Industry Divided in Battle for Free Electricity

(Bloomberg) -- A proposal to divide up the UK power market and unleash free electricity in the windiest parts of the nation is turning into a bitter fight between its biggest energy companies.

Whether to keep Britain’s electricity system as one national market or break it into regions with different prices is one of the consequential decisions looming for Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s government. There are potential benefits for consumers but major downsides for green power companies. Britain needs to deliver its climate goals and the impact of redrawing the market run to tens of billions of pounds.

“Both sides think they’re doing what’s right,” said Adam Bell, head of policy at consultancy Stonehaven who was previously in charge of strategy at the UK’s energy ministry. “There are a lot of people who stand to make or lose a lot of money either way.”

Today, Britain has a single wholesale price. But an ongoing review that’s expected to conclude early next year could split the UK into different zones each with a separate price, reflecting the balance of supply and demand and how much space there is on the grid. Areas like Scotland that have the most abundant wind power resources, but little electricity demand, would have a lower power price than the southeast of England, where it’s the opposite.

Influential voices from the UK’s biggest electricity supplier Octopus Energy and the country’s grid operator want to split up the market saying it would save consumers money, deliver on a Labour Party election promise to cut bills and give the British economy a boost. It could also spur building of new generation in England where local opposition has stymied investment, as well as potentially draw businesses to invest in far-flung parts of the country in order to access some of the world’s cheapest electricity.

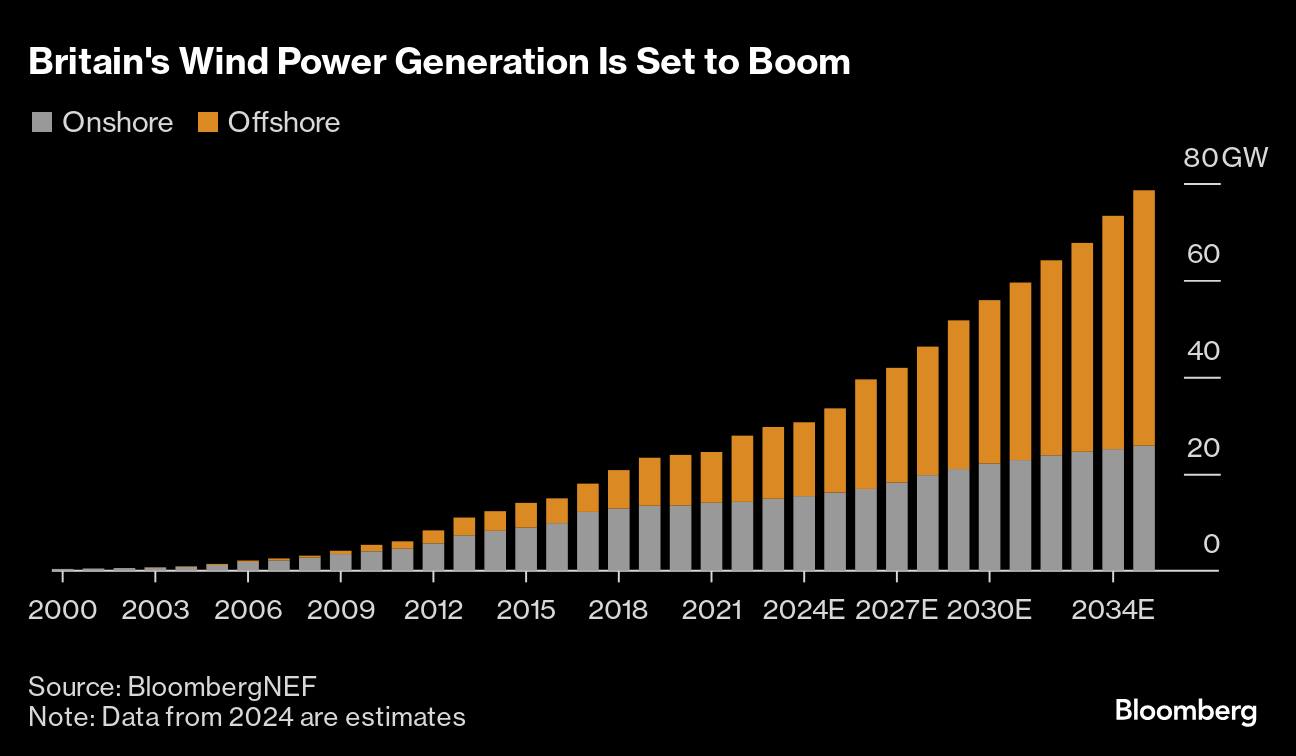

On the other side are the companies already investing billions to build and operate the country’s infrastructure. These portfolios are set to grow tremendously in the coming years as the government tries to drive investment into decarbonization at an unprecedented pace. Such a dramatic shift in regulation would upend investment cases, just as they’re being asked to speed up.

The government has to decide which side wins, after its Conservative Party-led predecessor avoided making a final decision earlier this year and then called an election. With either option, Starmer must deliver on the government’s goal to effectively eliminate carbon emissions from the country’s electricity grid by the end of the decade and lower consumer bills.

“We are reviewing responses to the consultation on reforming electricity markets and ensuring that any reform options taken forward focus on protecting bill payers and encouraging investment,” said a spokesperson from the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero.

More than 40% of the UK’s wind farms are in Scotland but less than 10% of demand. Whereas over a third of electricity consumption happens in London and the south of England. Costs are increasing to manage the mismatch between where electricity is produced and where it’s consumed.When it’s very windy and the grid can’t cope with the surge in supply, the operator will pay wind farms to stop generating. At the same time, in order to keep the lights on in the south of the country, the grid also has to pay gas-fired plants to fire up that are closer to demand.

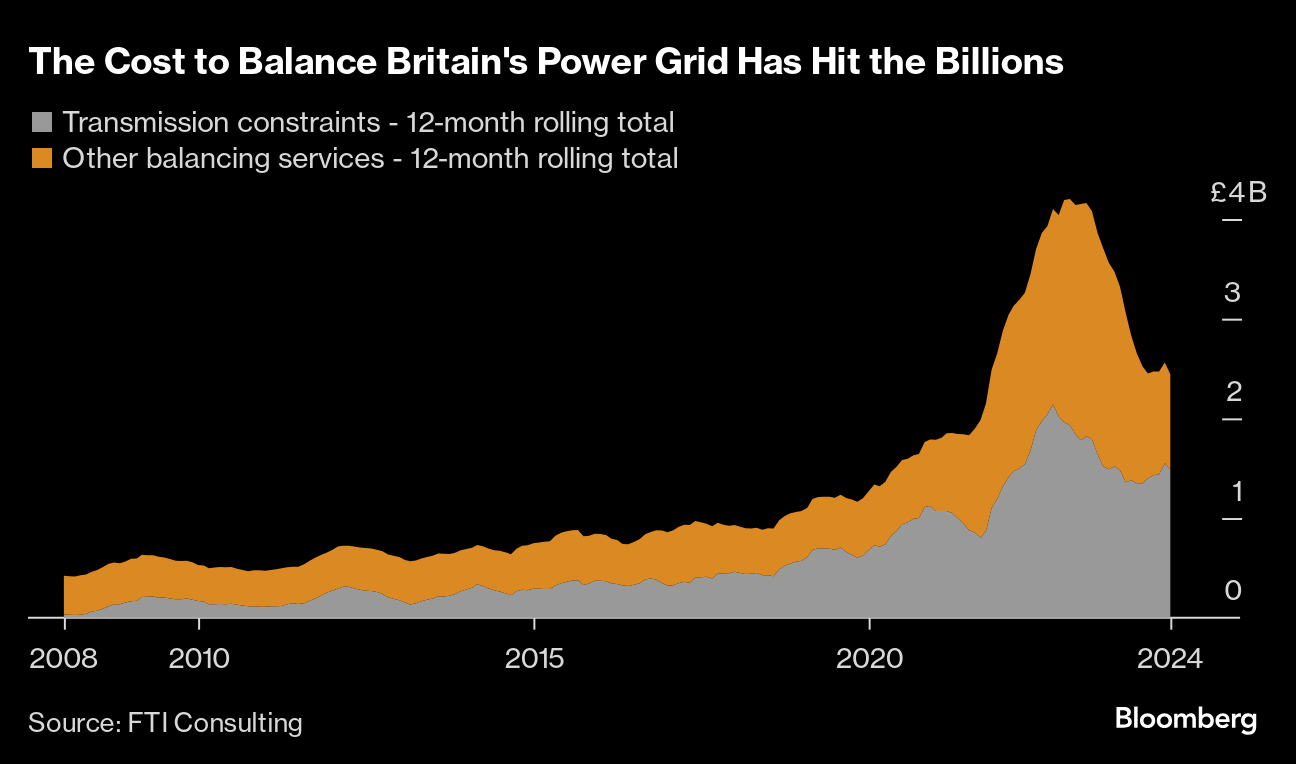

The cost to shut off certain generators rose to £2 billion ($2.6 billion) at the height of the energy crisis, up from about £100 million in 2010. While that figure has reduced with a fall in natural gas prices, costs were still about £1.5 billion in the 12 months to the end of March 2024. That could swell to more than £8 billion annually later this decade, according to analysis commissioned by the government.

“It’s unconscionable we’re adding billions to our bills in balancing costs and turning off wind farms and solar farms,” said Greg Jackson, chief executive officer of Octopus Energy. “Our founding mission was to drive energy costs down for customers. This is the only potential policy that will do that.”

Part of the problem is that the UK has already built 13 gigawatts of wind power in Scotland, mostly onshore and the grid is getting more clogged up trying to shift that supply. The one-price-system means Scottish households and companies don’t see the benefit of the low-cost power being produced on their doorstep and are effectively subsidizing consumers in the south.

The current market setup dates back to the late 1990s, when the regulator Ofgem decided to abolish the Electricity Pool of England and Wales. The pool, as it was known in the industry, started in 1990 and was considered one of the first competitive electricity markets in the world.

Generators submitted bids in daily auctions, with the cheapest ones getting to run. But costs rose and soon the regulator and government decided to change the system to try and lower consumer bills.

Among the people who worked on that effort was Jason Mann, an economist working in the late 1990s at a consultancy that later became part of PwC. One of the changes was the introduction of the balancing mechanism, which was seen as a way to reward flexible generation and drive efficiency.

A few years after the current system’s debut, a change was made that challenged the premise on which Mann and his colleagues had based their design: Scotland joined the electricity market. That added significant new generation that wasn’t backed up by sufficient grid to deliver the power to consumers in the south.

“No one on God’s sweet earth would have developed it like this if we’d known there would be large generation in Scotland,” Mann said in an interview. “You’d have been laughed at.”

Late last year Mann was commissioned to write a study of the impact of locational pricing for Ofgem.

Splitting Britain into several price zones could reduce the cost of running the power system by as much as £15 billion from 2030 to 2050, leading to a benefit of as much as £45 per British household every year, according to modeling commissioned by the government.

The downside of a change would be for electricity generators, particularly those in Scotland. Power prices would plummet in some places where firms have already invested in plants and have plans to expand.

That includes some 25 gigawatts of offshore wind projects in early stages of planning in Scotland, with an estimated investment requirement of close to £30 billion, according to Crown Estate Scotland, the authority that leased the seabed to developers. If built, those wind farms would nearly double the capacity currently operating in waters around the UK.

Such a fundamental change to the power market at this point could undermine investor confidence just as the government urges more and faster spending.

“When you look at the investment needed in offshore wind and onshore wind, saying to people part of the way through that investment that you’ll flip the entire trading system and pricing mechanism, you run a risk investment will delay,” said Keith Anderson, chief executive officer of Iberdrola SA’s Scottish Power, one of the country’s biggest renewable power and grid developers, as well as home energy retailers. “Doing something radical through that process you run a big risk of slowing down when we need to speed up.”

A switch to locational pricing would see higher electricity prices in London and the south of the country, which has the biggest concentration of people, politicians and media outlets. Lower costs to manage the system overall could still mean that bills would fall compared to a continuation of the current system. But that could be a complicated argument for members of parliament to make to their constituents.

“However you look at it, zonal pricing represents a profound change to the way our electricity markets operate,” said Adam Berman, director of policy and advocacy at industry group EnergyUK, which has members on both sides of the debate. Without proper analysis, “we run the risk of heading toward a market change that promises significant benefits but in practice doesn’t deliver.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.